It is because we hold shrImatI sandhyA jaina in high esteem as a hindU-minded journalist with an influencial reach and a tremendous potential, that we read with shock and disappointment the following lines coming from her pen:

“…in his teens in 1645 CE, he (shivAjI) began administering his father’s estate under a personalized seal of authority in Sanskrit, a hint that he envisaged independence and adhered to the Hindu tradition… The Peshwa, in contrast, accepted the Persian script under the influence of a Muslim courtesan, and narrow-mindedly refused to convert her to Hindu dharma despite her keenness to embrace the faith. As a result, the Marathas bowed to the Mughal emperor when they reached Delhi and missed a historic opportunity to re-establish Hindu rule; a classic case of muscle without mind, power without political sense! The rest is history.” (link)

Above is of course inaccurate as most readers would already know, but becomes difficult for us to ignore because it disrespectfully targets our favourite hero the first bAjIrAva, the ablest disciple of shivAjI.

Let us tackle the errors part by part, starting with the thing about Persian.

In context of the contemporary times, usage of Persian was a lesser evil, since it was the prevailing language of diplomacy and politics, and was used by most Hindu kings in their correspondences, before, during and after the times of cHatrapati and peshavA, up until English language elbowed out pArasIka tongue in status, eventually replacing it. Do we need to remind how gobinda siMha wrote zafarnAmah in Persian, and how raNajIta siMha had coinage and titles issued in Persian, and how most of the ambar archive is full of that language? Only those courts which had managed to keep themselves totally aloof were able to continue with the native languages.

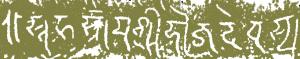

Even within shivAjI’s court, Persian titles and terms gave way to saMskR^ita ones very late in his regime. sabhAsada records that it was not until his rAjyAbhiSheka ceremony that the “Sanskrit titles were ordered to be used in future to designate their offices, and the Persian titles hitherto current were abolished.” Thus it was not until as late as cHatrapati’s coronation that ‘peshavA’ became mukhya-pradhAna, ‘majUmadAr’ became AmAtya, ‘waqiyA-navIs’ mantrI, ‘shurU-navIs’ sachiva, ‘dabIr’ sumanta, and ‘sar-i-naubat’ senApati. This too, of course under the guidance of the early paNDita-pradhAna-s, the predecessors of brilliant bAjIrAva. It was also by the guidance of his far-sighted peshavA-s that cHatrapati commissioned a handbook of working saMskR^ita too for the new-founded hindU state.

A whole chest of letters written by (the clerks of) shivAjI during the early days are in Persian. For instance, his famed letter sent for maharaja jayasiMha kacHavAhA during the famous siege, published by bAbU jagannAtha dAsa of vArANasI, speaks about establishing a Hindu collaboration to root out the Islamic tyranny: “Great Monarch mahArAjA jaisiMha, you are a valiant kShatriya, why do you use your strength to further the power of the dynasty of bAbUr? Why shed the costly Hindu blood to make the red-faced musalmAns victorious? … If you had come to conquer me, you would find my head humbly at the path you tread, but you come as a deputy of the tyrant, and I can not decide how I behave towards you… If you fight in championing our Hindu Religion, you shall find me your comrade in arms… Being so brave and valiant, it behoves you as a Great Hindu General to lead our joint armies against Emperor instead, and indeed let us go together and conquer that city of dillI, shed our blood instead in preserving the ancient religion which we and our ancestors have followed…”.

The above letter of shivAjI is, not in maharaTTI saMskR^ita or hindI, but in Persian, so are several others among shivAjI’s letters and orders. One must bear the contemporary situation in mind, before blaming bAjIrAva of “in contrast, accepting the Persian script under the influence of a Muslim courtesan”.

In fact peshavA-s, and in particular the rare visionary the original bAjIrAva along with his son, did the most meaningful service than anyone else since the days of vijayanagara empire, in reviving the devabhAShA. This is acknowledged even by the saMskR^ita-basher like Sheldon Pollock in his ‘The Death of Sanskrit’, where he quoted a stanza of a gujarAtI poet who “sensed that some important transformation had occurred at the beginning of the second millennium, which made the great literary courts of the age, such as Bhoja’s, the stuff of legend (which last things often become); that the cultivation of Sanskrit by eighteenth-century rulers like the Peshwas of Maharashtra was too little too late; that the Sanskrit cultural order of his own time was sheer nostalgic ceremony.”

Indeed, after kAshI it was pUnA which had emerged as the greatest center of saMskR^ita revival in the eighteenth century, under lavish patronage of the peshavA. A flourishing saMskR^ita university was established here by him, and a network of smaller schools, or Tol as they were called, encouraged throughout the empire, to educate the people in the devabhAShA. Many scholars were patronized here, producing several poetries and commentaries, as much as the political situation could afford.

mahAdeva govinda rANaDe writes in his ‘Introduction to the Peishwa’s Diaries’: “Reference has already been made to the Dakshina grants paid to Shastris, Pundits and Vaidiks. This Dakshina was instituted in the first instance by the Senapati Khanderao Dabhade, and when, on the death of that officer, his resources were curtailed, the charity was taken over by the State, into its own hands. Disbursements increased from year to year, till they rose to Rs. 60, 000 in Nana Fadnavis’ time. These Dakshina grants redeemed to a certain extent the reprehensible extravagance of Bajirao’s charities (refering to the son, not father). Learned Sanskrit scholars from all parts of India – from Bengal, Mithila or Behar and Benares, as also from tho South, the Telangan, Dravida and the Karnatic – flocked to Poona, and were honoured with distinctions and rewards, securing to them position throughout the country which they highly appreciated.”

Earlier this year we had accidentally run into a researcher from yavanadesha, who was doing some research about Greeks living in India in the Eighteenth century. He informed that peshavA had probably contracted a couple of Greeks from vArANasI, to help his pUnA scholars translate some of the Greek Classics of Homer into saMskR^ita. We can not say how true it is, but such impression does reflect on the services of peshavA in reviving saMskR^ita.

Now, coming to the “Muslim courtesan” part, reference here is to mastAnI, whom bAjIrAva “narrow-mindedly refused to convert to Hindu dharma”.

This is nothing short of blasphemy against the most genius Hindu Warrior and Strategist we have known since cHatrapati himself. mastAnI was a daughter of a Hindu father (some say of cHatrasAla himself) and a Moslem courtesan, married to bAjIrAv by cHatrasAla as an upapatnI, during bAjIrAva’s campaign in the region where he first wrested mAlavA from moghals, and a couple of years later, decisively hammered the Hyderabad Nizam in the classic battle of Bhopal, dashing his ambitions towards North for ever. Incidentally, it is from this victorious campaign that bAjIrAva returned not only with mastAnI, but also with elderly bhUShaNa, who was living his retired life at bundelakhaNDa, who accepted bAjIrAv’s invitation to relate to shAhUjI his reminisces of shivAjI. (The result was a poetry that came to be known as shiva-bAvanI, 52 pada-s dedicated to important milestones of shivAjI’s career; the famed “sivAjI na hoto tau sunnata hota sabakI” is from this work.)

It was not bAjIrAva because of whose “narrow mindedness” the re-conversion of mastAnI did not happen, but that of the ultra-orthodox brAhmaNa-s who had even out-casted bAjIrAv himself on accusations of eating meat, drinking wine, smoking tobacco and keeping Moslem wife etc. A son of bAjIrAva through mastAnI, named by bAjIrAv as kR^iShNarAva, was raised privately by him as a brAhmaNa and as per some pUnA traditions, even his thread-ceremony was performed at kasabA gaNapati, but he was not accepted as a Hindu by the more orthodox and was forced to live like a Moslem under the name of shamshIr bahAdur. This seed of bAjIrAv valiantly fought against abdAlI and fell in the battle of pAnIpat at the age of twenty-seven.

Orthodoxy’s rejection of bAjIrAva, his status not withstanding, was so strong that even the thread ceremonies and weddings of bAjIrAva’s legitimate sons were threatened to be boycotted if either bAjIrAv or mastAnI came anywhere near the ceremonies. bAjIrAv indeed did not attend these. bAjIrAva’s younger brother chimanAjI appA, the hero of vasaI, also never accepted mastAnI, and it is said that he even tried to eliminate her once when bAjIrAv was away leading the final battle of his life, in crushing the Hyderabad Nizam one more time before his untimely death; chimanAjI was restrained from his act only by the intervention of none less than shAhU himself.

However, in contrast contemporary records indicate that the peshavA-s themselves had quite an open outlook, especially about re-converting hindU-s that had under duress become musalmAna-s. mahAdeva rANADe provides some crucial data from peshavA’s diaries themselves: “ln those times of wars and troubles, there were frequent occasions when men had to forsake their ancestral faith under pressure, force, or fraud, and there are four well-attested instances in which the re-admission into their respective castes, both of Brahmins and Marathas, was not merely attempted but successfully effected, with the consent of the caste, and with the permission of the State authorities. A Maratha, named Putaji Bandgar, who had been made a captive by the Moguls, and forcibly converted to Mahomedanism, rejoined the forces of Balaji Vishvanath, on their way back to Delhi, after staying with the Mahomedans for a year, and at his request, his readmission, with the consent of the caste, was sanctioned by Raja Shahu. A Konkanastha Brahmin, surnamed Raste, who had been kept a State prisoner by Haider in his armies, and had been suspected to have conformed to Mahomedan ways of living for his safety, was similarly admitted into caste with the approval of the Brahmins and under sanction from the State. Two Brahmins, one of whom had been induced to become a Gosawee by fraud, and another from a belief that he could be cured of a disease from which he suffered, were readmitted into caste, after repentance and penance. These two cases occurred one at Puutamba, in the Nagar District, and the other at Paithan, in the Nizam’s dominions, and their admission was made with the full concurrence of the Brahmins under the sanction of the authorities.”

At one other place, rANAde provides some more important data that tells us about a much broader outlook the peshavA-s displayed in matter of the caste dynamics: “The right of the Sonars to employ priests of their own caste was upheld against the opposition of the Poona Joshis. The claim made by the Kumbhars (potters) for the bride and the bride-groom to ride on horse-back was upheld against the carpenters and blacksmiths who opposed it. The Kasar’s right to go in processions along the streets, which was opposed by the Lingayats, was similarly upheld. The right of the Parbhus to use Vedic formulas in worship had indeed been questioned in Narayanrao’s time, and they were ordered to use only Puranic forms like the Shudras. This prohibition was, however, resented by the Parbhus, and in Bajirao II’s time the old order appears to have been cancelled, and the Parbhus were allowed to have the Munja or thread ceremony performed as before. A Konkani Kalal or publican, who had been put out of his caste, because he had given his daughter in marriage to a Gujarathi Kalal, complained to the Peishwa, and order was given to admit him in the caste. In the matter of inter-marriage, Balaji Bajirao set the example by himself marrying the daughter of a Deshastha Sowkar, named Wakhare, in 1760.”

So much for the “narrow minded”, let us now come to the final and the most important mistake: “as a result, the Marathas bowed to the Mughal emperor when they reached Delhi and missed a historic opportunity to re-establish Hindu rule”. The blame is of course entirely misplaced, indeed a closer analysis will show that bAjIrAv’s energies were continuously driven towards striking down the mughal seat in dillI, and he was restrained from completely taking them out because of a bigger strategy and by shAhUjI’s command. One must read the desperate letters exchanged between him, the maharaTTA generals and envoyes in dillI court, at the time of the invasion by nAdirshAh from Persia. In one letter there is a clear reference of waiting for the “most perfect time” for “eradicating the moghal seat and placing the crown of the Emperor on the rANA of mevADa” (Refer to Vol II of A New History of Marathas by G S Sardesai).

shAhUjI felt, probably correctly, that this would be a misadventure, because maharaTTA power was spread too thin for any such move and he issued a clear policy statement to this effect to his officers. One must remember what even bhUShaNa says about bAjIrAva, at one place he calls bAjI a ‘bAja’ (hunt-hawk) who is eager to thrash the partridges of dillI but is obedient to his hunter-master of satArA.

But this encircling dillI, but not altogether taking out the puppet moghals, was a part of greater strategy as well as the currents of history.

First, there had been ill-ominous precedents of the unfortunate fate when hindU-s tried taking dillI openly: the sad case of short-lived enterprises of khusarU in fourteenth century and of himU in sixteenth, and bAjI would have hesitated to repeat that course in the Eighteenth.

Contrary to this jinxed option however, there was a more successful alternative model on the other hand, provided by the hindU history. How shivAjI’s father had once played a similar game succesfully with Adila nizAma shAha, whom he had protected as a puppet against jahAngIr, could have been more fresh in the memories of shAhU and bAjIrAv. Didn’t powerful grandfather of mahArANA pratApa, saMgrAma simha follow a similar approach in his own time to encircle dillI, by reducing its moslem occupant to a protectee and focusing instead on taking out the more potent jehAdI-s?

Therefore a more wise policy is what bAjIrAv and shAhU must have decided to follow, with following factors driving their strategy decision:

a) The center of gravity of jehAd had already shifted within moslem sphere, away from moghal imperial camp and towards independent moslem upstarts in va~Nga, hyderAbad and awadha, besides the rise of mercenaries like Afcrican Blacks and ruhillA-s etc. It was apparent that moghals had become toothless, and nothing was to be gained in practical terms by trying to eliminate the moghals, whereas there were several benefits of allowing them a status of a declared protectorate and go after the more potent jehAdI-s.

b) North Indian Hindus, especially rAjapUta-s, were still not ready to weild a common front, much less submit to a maharaTTA-s federal arrangement. sikh, jATa, and gorakhA were yet to become prominent on the radar.

c) It was therefore felt, quite correctly, that the policy has to be two fold: one, somehow not letting the jehAdI-s to unite under a common banner and join a common front. two: keeping rAjapUta-s in friendly relations and give them any reason to be alarmed. Both the ends were quite well served by positing of being a friend and protector of the dillI crown for the time rather than a predator threatening the replacement of moghal suzerainty over rAjapUtAnA by the maharaTTA one. Likewise, it disallowed a cry of unity under moghal banner within ghAzI aspirants, which was tested in the battle of bhopAla, where none came to the rescue of nizAm when bAjIrAv curtailed his feathers in North.

On this point, one should observe that the East India Company also imitated quite exactly the same strategy as bAjIrAva several decades after him, and with a complete success. Clive and Cornwallis imitated him in great detail, including posing to be a Hindu Saviour and protector of moghal crown, and friend of rAjapUta-s and so on, while they took out the more potent forces one by one, including the maharaTTA-s themselves!

d) Militarily too, bAjIrAva was confident of great mobility of maharaTTA cavalry, pioneered by him in now moving and fighting in open fields, long distances away from the base, and fashioned probably after taking cues on this point from changIz khAn! (read the eye-opening thriller on this subject by our AchArya of manasataraMgiNI). This mobility therefore could allow to quickly reach the theatre of operation over a much larger area and did not depend too much on a very fixed large encampment for maharaTTA forces, which further supported the view of letting dillI remain under moghal puppets, rather than requiring to be directly administered.

e) There was an administrative aspect too. Taking of dillI would require quite a lot of administrative machinery and overheads to be invested. shAhU was of the opinion that maharaTTA administration itself required to be more solidified before any such formal expansion has to become effective. This was quite a correct assessment too. Since the days of shivAjI, feudal structures like the jAgIradArI and mansabadArI, the hallmarks of moghal administration, were frowned upon. maharaTTA Generals used to be generally paid employees of state (although not necessarily the soldiers), no fiefs were allowed, no personal grant of lands distributed, no permanent subedArI-s given, no personal forts and fortesses allowed to be constructed. A letter of shivAjI written to his eldest son-in-law clearly reflects this where he declined the appeal of the latter for grant of a jAgIr to him, explaining his well-thought policy in this matter. But this system was probably not too scalable for a larger empire, and therefore we see it began to be slightly modified since bAjIrAv and shAhU, when a fort or zone was granted near ‘permanently’ to an officer hereditarily. He himself granted dhArA in MP to the pawAr Generals (dhAra, the old capital of bhojadeva was thought to be rightfully belonging to the pawAra-s, the descendants of the paramAra-s). But much later the vacuum that arose in the maharaTTA core, which later peshavA-s could not fill, saw the federalist system falter before it had properly stabilized, leading to the independence of sindhiyA, holkar, gAyakavADa, bhonsalA-s etc. leading to the total decline of the central authority. But at the time of bAjIrAva, the system was clearly not in place yet and maharaTTA nation could not have afforded to take up the overhead of administering dillI and its vassals, not to mention the effort needed in putting down the revolts it would have incited everywhere.

Thus the policy of encircling the moghals, reducing them to the point of extinction, slowly letting them get dismantled by themselves, but not outright eliminating them from dillI seat.

We hope shrImatI jaina shall correct the inadvertent but grave mistake of having insulted the great Hindu Hero.