“थीं चित्रकार भी स्त्रियाँ चित्रलेखा-सी कभी

अंकनकुशल नायक हमारे नाटकों मे हैं सभी!

“इतिहास काव्य पुराण नाटक, ग्रंथ जितने दीखते

सबसे विदित है, चित्र-रचना, थे यहाँ सब सीखते!

“हा! जो कलाएँ थीं कभी अत्युच्च भावोद्गारिणी

विपरीतता देखो कि अब वे हैं अधोगतिकारिणी!

“अपमान हाय! सरस्वती का सह रहे हम लोग हैं

पर साथ ही इस धृष्टता का पा रहे फल-भोग हैं!

“अज्ञान के अनुचर यहाँ अब फिर रहे फूले हुए

हम आज अपने आपको जो हैं स्वयं भूले हुए!

“Why! We used to once produce such fine painters as the renowned female artist Chitralekha; our ancient dramas invariably portray their heroes to be skilled in fine arts; Itihasa-s, Poetries, Purana-s, Drama, all declare in one voice how in the days of old each one used to be trained in the fine arts… Alas! The very arts which once used to be our mediums to express the loftiest, see the irony, are now degenerated to become the hallmarks of the basest! Lo, insult to Sarasvati herself we must patiently bear! But then the fruits of that perversity, who else but we alone should prepare to suffer? …But why do the followers of ignorance roam about puffed with glory? If not, that is, because we have ourselves verily forgotten our very own selves!”

Reading the fresh rounds of debate that followed the death of the late painter M F Husain, the above poetic anguish from the pen of the National Poet Shri Maithili Sharana Gupt surfaced in our memory. The legendary poet had written those lines in the first decade of the last century, at a time when the Hindu Art revival had yet not begun, but we were left wondering whether those lines did not precisely reflect the reality of our own times more accurately than ever?

In ancient India it would seem that painting was such a popular art, that anyone who did not know how to appreciate and judge an artwork was not considered groomed enough! kAlidAsa portrays in abhij~nAna shAkuntalam an amazing episode in the sixth part, where king duShyanta being lovesick for beloved shakuntalA, makes a portrait of her. And in the scene there is a character, who unable to appreciate the deeper rasa or bhAva of the painting to get to the true narrative of the painter, merely finds it “sweet and beautiful”. And important to note, kAlidAsa appoints this character to be a vidUShaka, a clown! The king and a couple of female assistant artists then educate the clown and make him cognize the deeper bhAva-s of pain, agony and love-ache that permeate the surficial forms of the painting howsoever sweet and beautiful.

bANabhaTTa says in his novel that every educated household used to cultivate at home a good vINA to play at, and a set of tUlikA-s to paint with, so widespread was the learning of arts in Hindu society. The connoisseurs of fine arts are often spoken of in the saMskR^ita literature, and respectfully called as kalA-vidagdha.

Of all types of arts – music and poetry, sculpture and drama – it is the chitra-kalA, the art of painting, which has always been considered the most precious lalita-kalA by the Hindu civilization. “कलानां प्रवरं चित्रं धर्मकामार्थमोक्षदं”, says viShNu-dharmottara, that of all the arts chief is the art of chitra-kalA, which helps one advance towards each object of human life. It is therefore, it says further, “यथा नराणां प्रवरः क्षितीशस्तथा कलानामिह चित्रकल्पः”, that like a monarch is amongst the men, so too is the art of painting amongst all the diverse formats of arts.

And like the other fields of knowledge, Hindus had also elevated and committed the art of chitra-kalA too into a most evolved philosophy and a faculty of knowledge. Thus we find in the Hindu sphere quite a diverse set of well-formed theories of painting. We find writers dedicating entire theses to exploring the theories of Art in such works as chitra-sUtra appended in the viShNu dharmottara, in samarAMgaNa sUtradhAra by rAjan bhojadeva the pramAra, in mAnasollAsa by chAlukya rAjan someshvaradeva who himself was an accomplished artist, aparAjita-pR^ichcHA a 12th century work by an artist-master from Gujarat, dedicated sections in a work entitled shilpa-ratna, and chitra-lakShaNa by nagna-jita. Besides these works that deal with the fine art in great detail, we also see descriptions about the theories of aesthetics and art of painting as peripheral discussions embedded in various purANa-s, dramas and works of poetry, as rightly alluded to by Shri Maithili Sharana Gupt.

It is thus even more unfortunate, as the poet lamented, that the very art which had received such celebration in Hindu universe, had to undergo such sorry decline, faring probably worst among all forms of arts during the centuries of existential civilizational distress. But the worst calamity is not so much of the art among the artists, but more so of the declined sense of art in the general Hindu public, which seems to have lost touch with the traditional sense of aesthetics and genuine appreciation for art, as also the poet has rightly diagnosed.

With such sentiments in our mind, in reaction to the eulogizing obituaries for M F Husain on one hand and damning criticism on the other, we decided to take a fresh look at his work, and here are our thoughts.

Husain was of as much a Muslim outlook as someone from the Shiite Bohra community can have. His ancestors were Arabs from Yemen who persecuted by the Sunnis had fled to India around after the downfall of Awrangzib. One can easily discern in Husain’s work, a distinct Bohra identity, which one might say, is more pronounced among Ismailis, their sibling sect, considered by Sunnis to be more of Hindus than Muslim. With belief in dashavatara and incarnation, religious books referring to vedas, especially the atharvan, alongside Quran; Quran itself they consider limited in scope of time; while there are Prophets, no particular Prophet is final for all times to come; their religious texts speaking of Rama, Krishna and Buddha alongside Muhammad, nor merely in missionary rhetoric but also in prayers; no obligation to visit Makka-Madina or observe fasts during Ramzan, and most do not, nor do they have obligatory five namazes a day; and whose mosques give out no azan to call momins to prayer, let him come who wants to come to the mosques which resemble more like gurudwaras where women and men sing prayers sitting on separate carpets in the same hall; and who are, no wonder, being given in Pakistan and elsewhere in the Islamic sphere, a treatment similar to the Ahmadias.

But we digress. Husain was brought up with as much a Muslim worldview of life as being from a Sulemani Bohra Shi’ite family would permit, and we can see this from his early themes that he chose to exhibit: Muharram (1948), Maulavi (1948), and Duldul Horse (1949): Muharram being the mourning of Shias, Duldul the horse of Imam Husain on the battle of Karbala so important to Shias, and his preference of Maulavi over Mawlana is also conspicuous. On his self-portraits till 1957, Husain continued to perceive his self-image with a black sulemani cap, which he had otherwise discarded already. In later period for many years, Husain would continue to paint on Islamic themes; calligraphy on watercolours etc., but in our estimation such works never had that kind of emotional force as he demonstrated in the early ones, and indeed, it is our estimation that the mental and emotional depth of Husain towards the Mohammedan themes continued to decline, if we shall only listen to his works. In fact we read in a recent interview of his, from earlier this year itself when he was engaged in a project commissioned in Qatar, that his object is not depiction of Islam but Arabic civilization. There is more to Arabia than Islam, said he.

Now, at a time when Husain began his career as an artist in the late 1930s, there were two main thought currents that were then on the ascendancy in the then contemporary art, besides the colonial British school which was already in decline. We find much confusion about these two schools among both the supporters of Husain and critics, so it would be pertinent to first understand the two separate nationalistic currents.

The first was svadeshI current, which was by then a mainstream force in all walks of national cultural life. Like in other fields, in art too, svadeshI group was aiming towards rediscovering the indigenous sense of aesthetics, rejuvenating the traditional artistic theories and progressing from there, and rejecting the alien. The ideology, intellectual inputs, and philosophical framework came from such scholars as Shri Ananda Coomarswamy and Shri Aurobindo, as well as a genuine Hinduphile British artist-scholar Dr. E B Havell. The result was a profound renaissance of Hindu art in the making, with such stalwarts as Abanindranath Thakur, Asit Haldar, Kshitindranath Majumdar, K Venkatappa, Sarada Ukil, Jamini Roy, Amrita Shergil, C Madhava Menon, Ramkinkar Baij, and above and more than all, Acharya Nandalal Basu, trying to nurture the sapling of genuine Hindu art again, and trying to water its deep roots. Because most of its painters were concentrated at Shanti Niketan, they came to be popularly known as the Bengal Art Renaissance group, though they never called themselves so; indeed in their vision was entire India and they had many non-bengalis among its stalwarts; they called themselves the svadeshI group.

Closely related to them in the stated objective of reviving the Hindu Art, but distinct from them in outlook and mental makeup, was another group of artists, most of whom were from the traditional painter families that had been attached through generations with the princely or business families, and which had kept intact in whatever form, the styles and formats of old. Their role model and inspiration was Raja Ravi Varma, who had already departed three decades back. Some of the representative products of this group are chitra-rAmAyaNa and the artworks of Gita Press Gorakhpur artists. Admirable as their efforts were and beauteous their product, they entertained no tendency of any fresh intellectual inquiry, no textual or visual scholarship, no philosophical or historical study of Hindu art; their aim was limited to simply creating attractive posters, calendars, and magazine art, on well-known religious or patriotic themes, improving only on the beauty of the form and style. They represent, to paraphrase the succinct words of Dr. S Radhakrishnan, that tendency of the decaying Hindu intellect that refuses to strike any new note at his vINA, simply repeating the tunes learned from ancestry, only improving on the volume; a tendency that had helped us save what we could save during the times of distress, but in times of progress, a burden! Most of these artists were concentrated in suburban cities of Maharashtra and UP, they are referred popularly as the Bombay Revivalist group.

If we were to use the language of the American art critic Clement Greenberg, this second group represented the popular kitsch while the former a genuine nationalist avant-garde. Modern Hindus would do well to clearly understand the difference between the two, because their ignorance allows Hindu-drohin leftists to distort the discourse and peddle their phony theories, and also because the same difference exists between the genuine and the pseudo nationalism in other walks of life too, including politics.

Now, also like in the other fields, in art too there was then emerging a marxist group, for whose votaries art was, like any other field, a medium to spread propaganda to bring about some utopian revolution as revealed in the marxist handbooks. In their ideological shibboleth they would treat both of the fore-mentioned as an impediment to their so called progress. Leader of this marxist group was a Goanese Christian, Francis Newton Souza, a card-carrying member of the Communist Party of India, who in the 1940s set up Progressive Artists Group, a front organization of the Communist Party.

These were the main currents prevalent when Husain came to Bombay to learn and pursue a career in art while earning his livelihood as a cinema poster painter.

Husain was actively persuaded by Souza and recruited to the Progressive group in 1947. Both the critics and the leftist supporters of Husain keep mentioning this point to support their respective arguments. Leftists, trying to aggrandize the school of committed marxists by subsumption, and critics to show how Husain was therefore against the nationalist current. But let us look at the facts again.

Apart from Souza, hardly any other artist member of the so-called Progressive group was committed to Leftism. And also apart from Souza, no well-known member was against the nationalist painters, also known as the Bengal group.

Let us read, for instance, what Sayed Haider Raza, a co-founder of the Progressive Group, himself says:

“…though some of my colleagues like Souza and others thought differently, I had the conviction that renaissance of art in Bengal was extremely important, not only in literature and music, but in painting as well. It was important because it brought our attention to our own culture. I mentioned painters like Abanindranath Tagore, Nand Lal Bose, Asit Kumar Haldar, Binod Bihari Mukherji and others. And I feel that what they did is important not only in the history of Indian art but also because they brought our attention to Indian painting.”

“Then there were books by Ananda Coomarswamy who brought to our notice many hidden things about Indian Art and Aesthetics.

[…] Souza was not interested in the renaissance of Bengal art, in painters like Nandlal Bose and others; he thought the vitality of our life was different. Our expression should be different. We should give a new direction. I did agree with this to a certain extent without undermining the importance of renaissance school of Bengal; even at that time I knew that three of the most important painters of the first half of the 20th century were the poet Rabindranath Tagore, Jamini Roy, and Amrita Shergil.” [“Passion: life and art of Raza”, by Sayed Haider Raza and Ashok Vajpeyi]

Raza remains even today a signature artist painting almost exclusively on geometric presentation of esoteric Hindu concepts, darshana-s, tantra, yoga etc., and is in our estimation, one of the important contemporary artist of our times.

This was Raza, the co-founder of the Progressives. But we read the same sentiment from Husain too. Below is from a 1997 article that Frontline, a leftist magazine, had printed based on his oral narrative:

“We had our own parallel national movement. We were part of the Progressive Artists Group; there were five or six painters in Mumbai and a few in Calcutta. We came out to fight against two prevalent schools of thought in those days, the Royal Academy, which was British-oriented, and the revivalist school in Mumbai, which was not a progressive movement. These two we decided to fight, and we demolished them.”

One should carefully note above that Husain is not talking about fighting against the genuine Hindu art renaissance group of Nandalal Basu etc, but specifically the Bombay revivalist group, which we have mentioned earlier. With that in our mind, let us hear Husain further:

“The movement to get rid of these influences and to evolve a language that is rooted in our own culture was a great movement, and one that historians have not taken note of. It was important because any great change in a nation’s civilisation begins in the field of culture.”

“The movement started in the 1930s with Souza, Raza and others. I joined in 1947. Our concern was to evolve not only art as a profession to make a living, but to do serious research to evolve a language for Indian contemporary art. It had to be rooted in our culture and all the points of reference had to be ours, but it had to use modern techniques as well. There was no point in painting like Indian miniatures, or like Ajanta and Ellora. The main difference between Indian art and Western art is that in the West, after the Renaissance, they had the Impressionists, then Cubism and so on. We, however, had already passed those stages. They were not necessary, because in our Indian folk art and tribal art, we had all these elements, and we have them even today. It is a living art form. After the Renaissance, artists in the West were concerned with depicting space and matter. We had already gone beyond that in our sculptures and paintings. When Michelangelo and others were trying to create the human form, we had passed that stage. The image of Nataraja is the highest form of art; it corresponded to the cosmos.“

Husain’s assessment of Indian Art having not only already seen those phases of progress but actually having evolved those to utmost maturity is absolutely right. We can read in mAnasollAsa, how the chAlukya rAjan deals in such detail with the diverse theories of painting that one can easily recognize many points of concordance with what the European masters would later discover, impressionism, naturalism and so on. In a commentary by bauddha scholar buddhaghoSha upon dhammasaMgani, a third century BCE pali text, the author describes a way of painting. Citing this, Prof Surendra Nath Dasgupta demonstrates how the Indian artists had also conceived of what the European masters would later call Expressionism, and that what buddhaghoSha describes merely in a few paragraphs in his commentary is a more perfect definition of Expressionism in art than what Croce would manage in a massive tome two millennia later!

Similarly, for a pristine example of the art-philosophy of Naturalism in the Hindu Art, see for instance how in meghadUtam, mahAkavi kAlidAsa has the love-sick yakSha describe his approach to creating a portrait of his long-seperated wife: “I try to satisfy my soul by trying to discover the expression of your beauteous shape in the beauty of nature. I look at the latA-s to seek your form and movement; I look into the eyes of startled deers to find similarity with your love-glances; I look at moon to seek your sweet face; and at the feathers of peacocks for your curls. But alas My Beloved, this nature fails to inspire my imagination in scale to your beauty that is etched in your picture on the walls of my heart.” An extremely pristine example of the artist in a dilemma between Naturalism and Expressionism, this stage Hindu artists had already seen, centuries before the European masters would discover it. Similarly, we can notice that what is discovered as Dynamism by the post-renaissance European masters later, as a way of representing movement by simultaneous multiple depiction of the same object, is openly evident in its full glory in the iconography of naTarAja’s arm-movement, or in Rahasalila painting of Kangra, as well as in the famous depiction of buddha ascending the staircase of buddhahood. For the Cubism likewise, see how the jaina architects were able to conceive of a very sophisticated synthesis of pure geometric play of shapes, repeated and patterned across multi-dimensional planes. If only had the European Cubist masters of last century, Picasso and Braque, visited Western India and seen the jaina designs at Shatrunjaya and Ranakpur, they would have immediately found for their Cubism a more sophisticated aesthetic connection with Hindu antiquity!

So we tend to agree with what Husain is saying. Let us continue with Husain’s narrative:

“The West claims modern art as its own. This is wrong. It is Eastern, they took it from Japan and from Africa. Because their media are strong, they have dominated the art scene.”

“Also, we do not have a single person, a writer, who has a historical vision of our culture and can make people aware of it. After Ananda Coomaraswamy, there has been no such person.“

Reader should take a note of Husain’s appeal to Coomaraswamy, and understand his frame of references.

“I am a misfit in the mainstream of contemporary Indian art. It has no relevance to our culture. Its points of reference are in the West, and that has to change. The problem with Indian contemporary art is the lack of a historical perspective. It is not only the painter, but even the general public that has lost touch with our rich heritage.”

“I had done paintings of Ramayana, about 80 paintings over eight years. We took them to villages near Hyderabad on a bullock cart. The paintings were spread out, and the people saw them, and there was not one question. In the city, people would have asked: Where is the eye? How can you say this is Ram? and so on. In the villages, colour and form have seeped into the blood. You put an orange spot on a stone and the people will say it is Hanuman. They would never ask where the eye was and so on. This is living art.”

The above is from 1997, when controversy had not yet been heard.

All we can discern from Husain’s verbal narrative in the above is that far from any Leftist sentiment, here is a painter who seeks, or at least claims to seek, a genuine Indian artist tradition.; whose frame of reference is Coomaraswamy not Croce and Picasso; who is tradition-sympathetic, interested in the genuine Hindu chitra-kalA.

That was Husain’s verbal narrative, now let us look at his visual narrative, as we should be able to understand the mind of an artist, a poet, a writer, better through his creation more than his verbal biographic narration, besides as they say, a picture can speak more eloquently than a thousand words.

So let us now get into his art, and for a moment detaching ourselves from the controversy try to understand his visual grammar first. By doing this is how we shall be able to also explore the answers like whether Husain had been deliberately disrespectful to Hindu devatA-s, and why if so, etc.?

Now as far as the criticism of Husain around the controversy is concerned, what is discomforting is the small sample size of Husain’s works being considered. Surely when the painter has created hundreds of pieces, it does not seem fair to only look at a dozen or so of his offending paintings. Then too, almost all the samples have come from a short span of about four middle years of 1970s, and few from 1996-97. For Husain, who had been active for over seven decades, we should look not only for a larger set, but also representative distribution over all the range of years, and understand his work as a whole, including and particularly those paintings that are not offending. And then we would be prepared to understand and analyze something about the offending ones too.

Now, there is only one precaution, indeed a preparation, that one must carry in one’s mind. We should remember that Husain was a modern painter. A modern painter by definition has his own visual grammar, different from the prevailing grammar with which audiences are familiar, therefore, one must be patient with any modern painter to really understand, if not like, the saundarya-bodha of that work. As to this difficulty of any modern artist, Clement Greenburg rightly observes that since a modern painter, “breaks up the accepted notions upon which must depend … the communication with their audiences, it becomes difficult. […] artist is no longer able to estimate the response of his audience to the symbols and references with which he works.”

kAmasUtra says, “सा कविता सा वनिता यस्याः श्रवणेन स्पर्शेन च, कवि हृदयं पति हृदयं सरलं तरलं च सत्वर भवति”, that, in short, a poem and a woman are good (for you) if they melt your heart. But not all poems and not all women can melt all hearts; does it also not depend upon the taste and aesthetic-sense of the perceiver for an art or poem to strike that rasa in his heart? Indeed as is well said by the medieval Hindi poet Bihari, ” मन की रुचि जेती जितै, तित तेती रुचि होय”, that is, his poems can not be liked by all, only those who have a similar aesthetic-liking (ruchi) in their heart that matches his, would find his poems beautiful (suruchi), and for the others it might even sound repelling (kuruchi), but he appeals to the audience to at least understand if not appreciate what he creates. So, in the similar vein, the precaution we need in studying Husain’s art is, to only be sympathetic and open and understanding, not judge it only by our personal aesthetic sense nor by the traditional norms and symbols; one may still appreciate or at least understand an art, a poem, even if one does not find it to their liking or taste; this would be the approach of our traditional rasaj~na AchAryas, and this is how let us look at Husain’s works.

So let us start, theme by theme. As an auspicious beginning, let us start with gaNesha, who seems to have much fascinated Husain and had been his favourite subject on canvas besides his horses. Following are some of the samples of his gaNesha:

1972:

1975:

Early 80s:

From 1984:

From 1993:

From 1998:

And in 1997, on the eve of the 50th Indian Independence day, It is gaNesha whom Husain invited on a symbolic tricolour:

Above are only some samples. There are hundreds (literally) of his colourful paintings and sketches and drawings devoted to gaNesha alone, and a lot more where gaNesha shares canvas with some other central themes. None of his gaNesha depictions seemed offending to our eyes even by any stretch. In fact we also read an interview, where he says he would begin any major painting by first drawing a gaNesha on the canvas, as an auspicious beginning. In some paintings of Husain, indeed gaNesha is just present lurking in some corner although themes are entirely different. Let us remember this fascination of Husain for gaNesha for we shall again refer to this later.

Let us now look at his depiction of the other Hindu deities.

Besides a painting of shiva-pArvatI from 1970s that has been included in the list of “offending”, we could see how Husain has depicted mahAdeva and gaurI on multiple occasions in a variety of styles, and still quite respectfully. Indeed Husain’s first major foray into depiction of Hindu deities started with his painting in early 1960s, titled by him as umA-maheshvara:

Another of his painting depicting the shiva family from the same decade:

Both of the above are aesthetically quite pleasing.

In this watercolour showing a street of Hyderabad in 70s, notice his depiction of umA-maheshvara on a film poster:

He again revisited umA-maheshvara in 70s in this one:

Below is his expression of ardha-nArIshvara form of umA-maheshvarau:

In the following watercolour from 1970s, he depicts shiva is in a female naTinI form, playing mR^ida~Nga and dancing, with kR^iShNa giving him company on flute:

That brings us to kR^iShNa, whom too Husain seemed to have quite adored as a subject, and whose depictions on his canvas have quite a strong emotional appeal. Some samples:

Gopala, 1972:

His depiction of Krishna Lila is not at all vulgar or obscene, indeed there is a strong romantic and mysterious appeal:

Same theme in a different style and format:

Krishna Lila, early 1980s:

And look at this quite powerful pArtha-sArathi presentation in the following oil painting:

In the above one should observe Arjuna shown ready to abandon his gANDIva and jump from the chariot (notice the depression on this side of the wheel); bi-colour sun represents the conflict between dharma and adharma; horses pulling in different directions representing confusion. kR^iShNa, not represented in form but commanding a central presence merely by the symbol; His tarjanI raised upright with sudarshana, and the famous words emitting in devanAgarI. Also do notice another fine point in the above. Because the width of the painting did not allow Husain to place kR^iShNa in the exact center of the painting geometrically, so he finds an artistic way to do it visually. He deliberately paints a different and paler background on the left side, so that kR^iShNa optically becomes the exact center of his painting.

There is another Husain painting on pArtha-sArathi theme, which is considered offending by some. Here it is, though we could not locate a higher resolution version:

One must carefully digest what the painter is depicting in the above. What he has used in the above is an idiomic Expressionist Morphism, using which he sends kR^iShNa to the background, like in the previous one, to participate in the theme symbolically, through a large dark palm making an upadesha-mudrA. Arjuna likewise in background with his bow is morphing into a figure in the foreground. This figure that dominates the foreground is of George Washington with the old version of American flag, leading the revolution and war for American Independence. The foreground is merely to lend the symbols and idiom to the real message which is embedded in the background. Here Husain is trying to portray the war of mahAbhArata as a revolution, a war of independence, of national political integration, and its hero, kR^iShNa, as a Revolutionary, a Warrior, a visionary Leader, and indeed the Founding Father to India as Washington is to the American nation.

Is that not the message of mahAbhArata? One who feels offended by this painting, we must say, has either little understanding of the epic, or can not appreciate such an obvious messages of this modern art, or more likely both.

There are plenty of paintings where Husain depicts kR^iShNa, and to our eyes all of them are quite pleasing, even emotional, and powerful. There are some paintings where a Mother Teresa like figure is shown tendering to boy-kR^iShNa. In Husain’s visual grammar, as we noticed how he utilizes Washington’s attributes to say something about kR^iShNa, likewise in depicting mother, he uses the symbol of a white dhoti with blue border, iconic of Mother Teresa, borrowing the symbol of generic motherhood. Rather than getting offended, we must first understand the painter’s methods.

While on mahAbhArata, following is Husain’s “Bhishma, or the 10th Day on Kurukshetra”, a watercolour on paper, from 1980s, depicting the grandsire:

In above too, notice the powerful usage of symbols. Half Sun, showing the wait of the pitAmaha for the uttarAyaNa; ten window panes, depicting the count of days; and a raised distorted point of illumination raised above the chest, depicting his will over death. Again a powerful depiction to our senses.

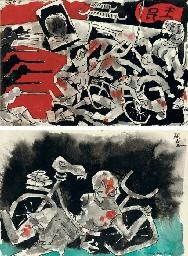

Then look at the following collagesque depiction on mahAbhArata themes:

Now devI-s.

What most people seem to have missed noticing is that after the understandably offending paintings, Husain had once again painted the same devI-s in a way that could not have offended any sane minded Hindu, or so we think; and could there be any better way for a painter to make a statement?

Also, those offending ones are not the only depictions of devI-s by Husain. Let us look at some.

This is a 2001 oil on canvas, depicting pArvatI as a mahArAShTrIya woman with a little gaNesha in her lap. This reminded us to the choLa sculptures which often depict her as a typical draviDa housewife carrying a tiny (and truant) gaNesha in one arm while managing ShaNmukha with the other.

This one is different in style but similar in sense:

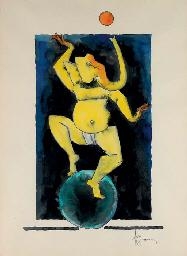

Following are his depictions of sarasvatI, already in mid 90s when there were no protests yet:

Above is the image of a modern Indian woman, her face, and the confidence that emits through her pose, are all very modern; and yet, she is dressed up in an entirely Indian dress, modern but distinctly Indian. And the painter also shows, symbolically by the flute and the music notes, how the traditional functions and duties of hers she does not abdicate.

This is Husain’s Sarasvati. You may like it, you may dislike it, but there is no disrespect here; indeed it shows only reverence of the painter; and indeed a way of Husain praying to sarasvatI for herself leading the modernization of Arts. Do not miss the symbolism of her lifting the Sun by her right arm, bringing a new dawn; and he is showing how easy it is for her to do, she is not even glancing towards it. And also notice another message: which type of modernization is Husain asking for sarsvatI to bring about? He is not asking sarasvatI to abandon vINA and take up Sitar or Guitar, he still wants her to only play vINA, but just that she now takes up the help of new techniques, new technology: she can print her favourite musical notes on paper! That the forms should be new, looks might be new, technique also new, but the essence continuing to be what has eternally been in the Hindu sphere: vINA remains!

This reminds us of the famous prayer to sarasvatI by Shri Suryakant Tripathi ‘Nirala’, a modernist Hindi poet, who is asking sarasvatI to make everything anew, only the old vINA remains and she remains:

“नव गति नव लय, ताल छ्न्द नव,

नवल कण्ठ नव जलद मन्द रव

नवनभ के नव विहगवृन्द को,

नव पर, नव स्वर दे

वर दे, वीणा-वादिनि, वर दे!

प्रिय स्वतंत्र रव अमृत मंत्र नव भारत मे भर दे!”

[New Rhythms, New Tunes, New Beats, Meters New

New voices, New clouds of imagination, Melodies New,

New Chirping and New Feathers to the New Birds on a Horizon New,

So Bless O Player of Vina, Bless that –

With a Nectar of Newness, is filled anew my Beloved Bharat independent New!]

We are with M F Husain in the prayer.

Following is his ‘Sita and the Golden Deer’, from 1991:

Some three depictions of his Hanuman have caused much protests, and understandably so, but let us also look at his other depictions of Hanuman and see them from the eyes of how a modern painter would have looked at the subject.

This above one has also caused some offense as “Hanuman” is shown in such a disgraceful posture. But this is how we read it. First off, one must understnad that the scene is depicting the vAnara-s bringing stones for the setu-bandhana. The watercolour above, depicts not hanumAna but a vAnara (do observe the differences in form, colour, etc.), plucking a huge rock from its base, lifting it up and placing on his left shoulder. We do not see any offense meant in this.

The below watercolour is Husain’s depiction of a Hanuman shrine with female figures performing their devotion:

This below painting has also been considered offensive my some people:

But those who consider the above offensive do not observe the message of it. Here we see a male figure and a female, making a vartula, which is rotating in a whirl with a small Hanuman in its center. The vartula of male and female would easily remind one of the famous Chinese dvaita motif of Yin and Yang. The yang on top, that is the well-formed muscular body, and yin, the female on the bottom. What the painter shows here is the make up and conception of Hanuman, which is why Hanuman is being shown in his infancy; on one side you have the powerful masculine side of his, he is vajra~Nga after all, but on the other side, equally dominant feminine qualities of Hanuman, that is, his devotion, service, sublimity and wisdom; both sides combining to make the concept of what Hanuman is. That is how we read this modern painting.

Below is a painting of his, which he titled as “Vedic”, collagesque depiction of the Hindu religious traditions.

Let us now explore an important attribute of Husain’s grammar, his attitude towards and depiction of Brahmins. After all he is accused of having insulted Hindus by showing a naked Brahmin together with a fully clothed Sultan; so let us try to understand that painting by first going through Husain’s other portrayals of brAhmaNas.

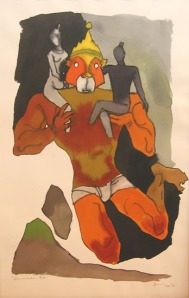

This one is entitled ‘Brahmin’; it is from 1980s:

In the above, do observe the aesthetic sense behind the abstract. Husain depicts a mere head as the brahmin, quite like the vaidika imagery of brAhmaNa being the shira of the cosmic puruSha. Center of the painting, locationally and visually, is at the base of the nose with brightness flowing upwards from Aj~nA illuminating the tall forehead. The eyes are silent and content yet commanding, lips are thin but not sensuous, face is lean without luxurious cheeks; it can easily remind a traditional Hindu of a virtuous sadAchArin brAhmaNa. Then do not miss at the bottom, an almost straight, thick line, in same colour that dominates the face, cutting across the width of the base, and on this line the brAhmaNa rests. By this line, Husain is trying to depict a boundary, which represents the maryAdA, the borders and code of conduct that a Brahmin can not cross, which governs the entire life of a Brahmin; and that is why this line is the very base on which the whole existence of the Brahmin rests, if the line goes, the Brahmana falls!

What a powerful Art!! mahAkavi bhAsa would have said, as he does in his drama dUtavAkyam, “अहो अस्य वर्णाढ्यता, अहो भावोपपन्नता, अहो युक्तलेखता, अहो दर्शनीयोयम चित्रपटम!”

A very powerful portrayal of the abstract concept of brAhmaNa is what we find painted by Husain here. One who can not demystify this one and has been calling him a blasphemer is himself one and must apologize to Husain! This is one of the best we have seen!

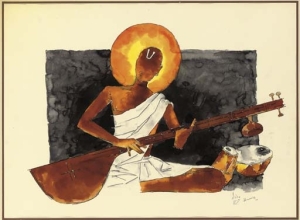

This another one is from late 80s, an untitled watercolour on paper, depicting a brAhmaNa playing on a vInA:

This indeed is a very powerful painting we should say. The halo, the tilt of head, the tanmayatA, the light over darkness!

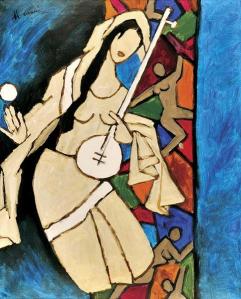

Another depiction of a Brahmin playing vINA, an abstract from 1998:

The above is quite powerful if one understands the context and Husain’s grammar. This one he had painted after attending a music concert by vocalist Maestro paNDita Bhimsen Joshi. The photo-frame is Husain’s symbol to represent the continuation of a past reality into the present, and one can easily understand how. There are two faces of the brAhmaNa, one facing frontally in the picture and playing the vINA, represents the old, the other face, turned to the right but with open lips represents the modified continuity of the same body into present. The vINA and the peacock, in symbol representing sarasvatI’s kalA, permeate across the two levels.

In 1970s, Husain had gone to attend a vaidika atirAtra in kerala. This below is his modernist portrayal of the homa, which he titles, “Performance of Fire”.

In the above abstract, the sacred Fire is represented simply by the well-understood male-motif of Hindu iconography, an up-pointing triangle. Notice the banner on which Fire is represented has the geometrical steps, and the banner itself stands for the yaj~nashAlA. Man and woman holding up the banner are the yajamAna, who have carried this Fire (from their home), signifying how it is done and that is how it should be. The brAhmaNa shown playing on mR^idaMga represents the singing of vaidika uchchAra. The masked kathakalI dancer in the left background, stands for the elaborate rejoicing and fanfare that surrounds the phenomenon. Also observe that Husain signs his name on the top right, not in his usual devanAgarI nor English, but in Malayalam, which is, in our eyes, Husain’s tribute to kerala for its exclusive contribution of continuing the ritual.

This one below is Husain’s expression to a traditional Tamil Brahmin household in contemporary times:

Now let us look at some more where Husain depicts a Brahmin in social contexts, which will also tell us about what Husain thought of the social role of the brAhmaNa.

The above darkish watercolour on paper is also from the same period. There are multiple human figures, however the central and imposing figure is of a brAhmaNa. This brAhmaNa is the only figure which besides being central and the largest, is given a chair to sit on, and reads from a news paper. All other figures, a woman with specs with back turned to us, a fisherman leaning on a coconut tree, some tribals, and other figures in the background, are all reading a newspaper too. The message of the painting is the spread of knowledge, education, culture all round the nation to all sections, and alludes to the central role of brAhmaNa for it. It is only temporally situated in a malayalIya landscape as Husain had painted it when it was announced that Kerala had achieved 100% literacy. It tells us how Husain viewed the brAhmaNa-s.

With the above themes in mind let us now look at another one in which Husain positions Brahmins in a social context. This below was created by Husain in 1981, using it would seem ink pen and sketch on paper, and has been left untitled:

This is very interesting, and may even seem somewhat intriguing if we do not understand Husain’s concepts and symbols, which we hope we understand to some degree by now. In the above, we see a Brahmin being in the exact center of the sketch with a lady seated by his left, who is neatly dressed up in a traditional Hindu attire, sari, bangles, ma~Ngala-sUtra, bindi, and veNI in her hair; she is holding up in her raised left arm a plate with flower-ornaments, which are apparently for the deities, for that is why the plate is raised high up. On the left, we notice a distorted and convoluted wheel in the background, with exactly twenty-four spikes, by which our painter seems to be representing the cycle of time, the kAla-chakra. Exactly from the center of this time-wheel has, as if emerged all of a sudden, this other lady looking like a Hollywood animation character, wearing western dress, boots, mini shorts, a fancy hat and a face mask. Her posture is threatening and aggressive, and has in her right arm a pistol, pointed at the Brahmin couple. The Brahmin has his right arm raised defensively, as if in protection for his wife. The face of Brahmin lady itself only shows shock and astonishment. The Brahmin’s face is turned towards the western lady and his neck bent in a vulnerable way.

The temporal meanings aside, the real message of Husain from the above is very easily discernible and displays Husain’s take on the conflict of westernization with our traditional ethos and way of life. Do observe also, that Husain signs his name on the left bottom, not in his usual Devanagari but in Tamil, which too says something. Hope the readers will have enough imagination to appreciate what Husain is saying.

So we have seen in all the above portrayals of Brahmin by Husain, how for him, Brahmin does not merely stand for a “Brahmin” alone, but represents on his canvas the ancient Hindu culture and civilization, knowledge, tradition, higher intellect, and nobleness. In the last one, that is what is under invasion by the aggressive cultural enemy, is what he is saying.

With this component of Husain’s visual grammar in mind, along with his respectful attitude that we have seen towards the Brahmin, let us again look at this supposedly anti-Hindu and insulting painting of his:

We now know already, how Brahmin stands for the Hindu civilization; it does not take a poets imagination to see that the naked is also an attribute of the vulnerability. Then we have an aggressive Sultan of threatening appearance, of almost equal in size to that of the naked Brahmin, but now edging beyond him. Dominant object on the canvas is a large sword in his right grip, and the Sultan almost ready to attack. And worst of all, the Brahmin, that is the Hindu civilization, is looking the other way, ignorantly.

Must it be explained in words what Shri M F Husain is visually depicting? Indeed like the brAhmaNa figure in the painting, one must have his eyes turned the other way, or one must be blind by imagination, to not understand what the painting is so openly telling us. Also, it is not without a reason that our painter has left this painting untitled, to keep it vague, and let only those of his audiences understand it who know how to understand it. But how blind the Hindus are!

While at it, let us also look again at Husain’s supposedly insulting painting of Bharatamata. She is shown in this like a vulnerable mother with ghungharu tied on her feet and she is being charged at by mad bulls, and the painting is torn from the middle in two pieces upside down. This one Husain had painted day after the Ghazi attack on Mumbai, and had titled “Rape of India”. One who can not understand the anguish of the painter in it and rather takes it as insult to Bharatmata, has little understanding of art.

While the above painting shows the painter’s anguish, the below, which Husain had painted in 1971 after India had crushed Pakistan in the Bangladesh war, easily has, to our eyes, a sense of jubilation:

In the above, some had felt he had depicted Indira Gandhi as Durga, which is possible, and is not out of the ordinary when Shri M S Golwalkar and Vajpayee had also mentioned Indira Gandhi in a similar vein. (Also, let us mention here, at the cost of diversion, that the same liberals who were damning the Hindus for feeling offended, in the recent years, had their liberal predecessors themselves expressing outrage at Husain’s naked portrayal of Indira Gandhi, and as Durga. They would do well to read up the archives.)

Now let us look at another social context on Husain’s canvas. This below is another untitled acrylic on canvas, from 2002:

Let us first observe the background. We see two full and two partial female figures as if struggling and climbing on a rock. The female figures are of distinct Indian bodies, brown skin to highlight their Indianness. On the foreground is the dominating figure, that is of Mira, beautifully poised, emitting sure confidence and purity. She is tilted towards these climbing figures, as if watching over them as a guardian. With her left arm she is playing her iconic ektara while at the same time, in a very feminine way, holding her upper dress, in a very India-like feminine sense. Her right palm is raised in abhaya-mudrA saying ‘fear not’, and the direction of her palm is such that tarjanI, the index finger, is pointing straight towards the moon, as if encouraging the climbing females to such heights. This is M F Husain’s message to the Indian feminists: Mira, not ‘burn-the-bra’, represents the Indian women’s aspiration for progress. We find it very powerful and meaningful painting.

In 1989, Husain painted the following painting, entitled “Fallen Bicycles of Tiananmen”, while the Indian lefty worthies were busy justifying the massacre of students by China.

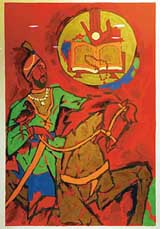

In the aftermath of the Delhi anti-Sikh riots, he painted “Guru Gobind” in solidarity with the Sikhs:

In tribute to Lokmanya B G Tilak, Husain painted “Svarajya”, which was adopetd as a postal stamp. In this he displays Tilak as the most prominant figure of the struggle for Swarajya, etching his famous words in Devanagari. Also notice the Lion figure behind Tilak. This is Husain’s way of giving the honor to the ‘Bharata Kesari’, that Tilak was.

Below are some of his depiction to Hindu festivals, landscapes and so on:

Holi, 1960s:

The landscapes of Varanasi, 1980s

In the end, having heard Husain in his own words both verbal and visual, we don’t think he was either a pervert or an anti-Hindu. We do have now a new-found respect for his art, in our eyes he was a good artist, who did have a connection with the Hindu roots.

What about those paintings of his, one might ask, which are quite offending? We shall say, those are certainly offending, particularly three of those paintings, one each of Sarasvati, durgA, and lakShamI, and then one or two more; but we shall quickly add, it was clearly not the painter’s intention to hurt or offend, nor was he a pervert nor a jehadi. We also think that those paintings do not define who he was, rather his hundreds of the other good ones do. What is more, looking at those paintings of his in the new light and through the eyes of the Hindu art, we can now understand how and why he painted those and gone astray there. We shall try to explore that aspect from the perspective of the Hindu chitra-shAsta, hopefully sometime in a subsequent post.

This below is his final self-portrait that is available. It seems he saw himself as a chitrakAra perhaps of the Gupta era or bhojadeva era, only with a brush that is modern rather than the old one (usually made of the hair of male calf from behind his ears and bamboo shoot). Notice a subtle photo frame like presentation with two vertical lines and which he is coming out of. This is his self-image. He perhaps felt like a traditional Hindu artist from the golden eras of Hindu art, who has stepped into the times that are ahead of us, thus taking the old tradition to the new times.

We wish that the Atman of Shri M F Husain, a much misunderstood artist, would fulfill its desires, and find happiness, evolution, peace. ॐ शम.

Continues to Part 2 here.

Posted on June 17, 2011 at 12:33 pm in Art & Sculpture, Commentary, Culture, Scripture, Tradition | RSS feed

|

Reply |

Trackback URL

[Part 1] M F Husain in a New Light: A Hindu Art Perspective

by Sarvesh K TiwariReading the fresh rounds of debate that followed the death of the late painter M F Husain, the above poetic anguish from the pen of the National Poet Shri Maithili Sharana Gupt surfaced in our memory. The legendary poet had written those lines in the first decade of the last century, at a time when the Hindu Art revival had yet not begun, but we were left wondering whether those lines did not precisely reflect the reality of our own times more accurately than ever?

In ancient India it would seem that painting was such a popular art, that anyone who did not know how to appreciate and judge an artwork was not considered groomed enough! kAlidAsa portrays in abhij~nAna shAkuntalam an amazing episode in the sixth part, where king duShyanta being lovesick for beloved shakuntalA, makes a portrait of her. And in the scene there is a character, who unable to appreciate the deeper rasa or bhAva of the painting to get to the true narrative of the painter, merely finds it “sweet and beautiful”. And important to note, kAlidAsa appoints this character to be a vidUShaka, a clown! The king and a couple of female assistant artists then educate the clown and make him cognize the deeper bhAva-s of pain, agony and love-ache that permeate the surficial forms of the painting howsoever sweet and beautiful.

bANabhaTTa says in his novel that every educated household used to cultivate at home a good vINA to play at, and a set of tUlikA-s to paint with, so widespread was the learning of arts in Hindu society. The connoisseurs of fine arts are often spoken of in the saMskR^ita literature, and respectfully called as kalA-vidagdha.

Of all types of arts – music and poetry, sculpture and drama – it is the chitra-kalA, the art of painting, which has always been considered the most precious lalita-kalA by the Hindu civilization. “कलानां प्रवरं चित्रं धर्मकामार्थमोक्षदं”, says viShNu-dharmottara, that of all the arts chief is the art of chitra-kalA, which helps one advance towards each object of human life. It is therefore, it says further, “यथा नराणां प्रवरः क्षितीशस्तथा कलानामिह चित्रकल्पः”, that like a monarch is amongst the men, so too is the art of painting amongst all the diverse formats of arts.

And like the other fields of knowledge, Hindus had also elevated and committed the art of chitra-kalA too into a most evolved philosophy and a faculty of knowledge. Thus we find in the Hindu sphere quite a diverse set of well-formed theories of painting. We find writers dedicating entire theses to exploring the theories of Art in such works as chitra-sUtra appended in the viShNu dharmottara, in samarAMgaNa sUtradhAra by rAjan bhojadeva the pramAra, in mAnasollAsa by chAlukya rAjan someshvaradeva who himself was an accomplished artist, aparAjita-pR^ichcHA a 12th century work by an artist-master from Gujarat, dedicated sections in a work entitled shilpa-ratna, and chitra-lakShaNa by nagna-jita. Besides these works that deal with the fine art in great detail, we also see descriptions about the theories of aesthetics and art of painting as peripheral discussions embedded in various purANa-s, dramas and works of poetry, as rightly alluded to by Shri Maithili Sharana Gupt.

It is thus even more unfortunate, as the poet lamented, that the very art which had received such celebration in Hindu universe, had to undergo such sorry decline, faring probably worst among all forms of arts during the centuries of existential civilizational distress. But the worst calamity is not so much of the art among the artists, but more so of the declined sense of art in the general Hindu public, which seems to have lost touch with the traditional sense of aesthetics and genuine appreciation for art, as also the poet has rightly diagnosed.

With such sentiments in our mind, in reaction to the eulogizing obituaries for M F Husain on one hand and damning criticism on the other, we decided to take a fresh look at his work, and here are our thoughts.

Husain was of as much a Muslim outlook as someone from the Shiite Bohra community can have. His ancestors were Arabs from Yemen who persecuted by the Sunnis had fled to India around after the downfall of Awrangzib. One can easily discern in Husain’s work, a distinct Bohra identity, which one might say, is more pronounced among Ismailis, their sibling sect, considered by Sunnis to be more of Hindus than Muslim. With belief in dashavatara and incarnation, religious books referring to vedas, especially the atharvan, alongside Quran; Quran itself they consider limited in scope of time; while there are Prophets, no particular Prophet is final for all times to come; their religious texts speaking of Rama, Krishna and Buddha alongside Muhammad, nor merely in missionary rhetoric but also in prayers; no obligation to visit Makka-Madina or observe fasts during Ramzan, and most do not, nor do they have obligatory five namazes a day; and whose mosques give out no azan to call momins to prayer, let him come who wants to come to the mosques which resemble more like gurudwaras where women and men sing prayers sitting on separate carpets in the same hall; and who are, no wonder, being given in Pakistan and elsewhere in the Islamic sphere, a treatment similar to the Ahmadias.

But we digress. Husain was brought up with as much a Muslim worldview of life as being from a Sulemani Bohra Shi’ite family would permit, and we can see this from his early themes that he chose to exhibit: Muharram (1948), Maulavi (1948), and Duldul Horse (1949): Muharram being the mourning of Shias, Duldul the horse of Imam Husain on the battle of Karbala so important to Shias, and his preference of Maulavi over Mawlana is also conspicuous. On his self-portraits till 1957, Husain continued to perceive his self-image with a black sulemani cap, which he had otherwise discarded already. In later period for many years, Husain would continue to paint on Islamic themes; calligraphy on watercolours etc., but in our estimation such works never had that kind of emotional force as he demonstrated in the early ones, and indeed, it is our estimation that the mental and emotional depth of Husain towards the Mohammedan themes continued to decline, if we shall only listen to his works. In fact we read in a recent interview of his, from earlier this year itself when he was engaged in a project commissioned in Qatar, that his object is not depiction of Islam but Arabic civilization. There is more to Arabia than Islam, said he.

Now, at a time when Husain began his career as an artist in the late 1930s, there were two main thought currents that were then on the ascendancy in the then contemporary art, besides the colonial British school which was already in decline. We find much confusion about these two schools among both the supporters of Husain and critics, so it would be pertinent to first understand the two separate nationalistic currents.

The first was svadeshI current, which was by then a mainstream force in all walks of national cultural life. Like in other fields, in art too, svadeshI group was aiming towards rediscovering the indigenous sense of aesthetics, rejuvenating the traditional artistic theories and progressing from there, and rejecting the alien. The ideology, intellectual inputs, and philosophical framework came from such scholars as Shri Ananda Coomarswamy and Shri Aurobindo, as well as a genuine Hinduphile British artist-scholar Dr. E B Havell. The result was a profound renaissance of Hindu art in the making, with such stalwarts as Abanindranath Thakur, Asit Haldar, Kshitindranath Majumdar, K Venkatappa, Sarada Ukil, Jamini Roy, Amrita Shergil, C Madhava Menon, Ramkinkar Baij, and above and more than all, Acharya Nandalal Basu, trying to nurture the sapling of genuine Hindu art again, and trying to water its deep roots. Because most of its painters were concentrated at Shanti Niketan, they came to be popularly known as the Bengal Art Renaissance group, though they never called themselves so; indeed in their vision was entire India and they had many non-bengalis among its stalwarts; they called themselves the svadeshI group.

Closely related to them in the stated objective of reviving the Hindu Art, but distinct from them in outlook and mental makeup, was another group of artists, most of whom were from the traditional painter families that had been attached through generations with the princely or business families, and which had kept intact in whatever form, the styles and formats of old. Their role model and inspiration was Raja Ravi Varma, who had already departed three decades back. Some of the representative products of this group are chitra-rAmAyaNa and the artworks of Gita Press Gorakhpur artists. Admirable as their efforts were and beauteous their product, they entertained no tendency of any fresh intellectual inquiry, no textual or visual scholarship, no philosophical or historical study of Hindu art; their aim was limited to simply creating attractive posters, calendars, and magazine art, on well-known religious or patriotic themes, improving only on the beauty of the form and style. They represent, to paraphrase the succinct words of Dr. S Radhakrishnan, that tendency of the decaying Hindu intellect that refuses to strike any new note at his vINA, simply repeating the tunes learned from ancestry, only improving on the volume; a tendency that had helped us save what we could save during the times of distress, but in times of progress, a burden! Most of these artists were concentrated in suburban cities of Maharashtra and UP, they are referred popularly as the Bombay Revivalist group.

If we were to use the language of the American art critic Clement Greenberg, this second group represented the popular kitsch while the former a genuine nationalist avant-garde. Modern Hindus would do well to clearly understand the difference between the two, because their ignorance allows Hindu-drohin leftists to distort the discourse and peddle their phony theories, and also because the same difference exists between the genuine and the pseudo nationalism in other walks of life too, including politics.

Now, also like in the other fields, in art too there was then emerging a marxist group, for whose votaries art was, like any other field, a medium to spread propaganda to bring about some utopian revolution as revealed in the marxist handbooks. In their ideological shibboleth they would treat both of the fore-mentioned as an impediment to their so called progress. Leader of this marxist group was a Goanese Christian, Francis Newton Souza, a card-carrying member of the Communist Party of India, who in the 1940s set up Progressive Artists Group, a front organization of the Communist Party.

These were the main currents prevalent when Husain came to Bombay to learn and pursue a career in art while earning his livelihood as a cinema poster painter.

Husain was actively persuaded by Souza and recruited to the Progressive group in 1947. Both the critics and the leftist supporters of Husain keep mentioning this point to support their respective arguments. Leftists, trying to aggrandize the school of committed marxists by subsumption, and critics to show how Husain was therefore against the nationalist current. But let us look at the facts again.

Apart from Souza, hardly any other artist member of the so-called Progressive group was committed to Leftism. And also apart from Souza, no well-known member was against the nationalist painters, also known as the Bengal group.

Let us read, for instance, what Sayed Haider Raza, a co-founder of the Progressive Group, himself says:

Raza remains even today a signature artist painting almost exclusively on geometric presentation of esoteric Hindu concepts, darshana-s, tantra, yoga etc., and is in our estimation, one of the important contemporary artist of our times.

This was Raza, the co-founder of the Progressives. But we read the same sentiment from Husain too. Below is from a 1997 article that Frontline, a leftist magazine, had printed based on his oral narrative:

One should carefully note above that Husain is not talking about fighting against the genuine Hindu art renaissance group of Nandalal Basu etc, but specifically the Bombay revivalist group, which we have mentioned earlier. With that in our mind, let us hear Husain further:

Husain’s assessment of Indian Art having not only already seen those phases of progress but actually having evolved those to utmost maturity is absolutely right. We can read in mAnasollAsa, how the chAlukya rAjan deals in such detail with the diverse theories of painting that one can easily recognize many points of concordance with what the European masters would later discover, impressionism, naturalism and so on. In a commentary by bauddha scholar buddhaghoSha upon dhammasaMgani, a third century BCE pali text, the author describes a way of painting. Citing this, Prof Surendra Nath Dasgupta demonstrates how the Indian artists had also conceived of what the European masters would later call Expressionism, and that what buddhaghoSha describes merely in a few paragraphs in his commentary is a more perfect definition of Expressionism in art than what Croce would manage in a massive tome two millennia later!

Similarly, for a pristine example of the art-philosophy of Naturalism in the Hindu Art, see for instance how in meghadUtam, mahAkavi kAlidAsa has the love-sick yakSha describe his approach to creating a portrait of his long-seperated wife: “I try to satisfy my soul by trying to discover the expression of your beauteous shape in the beauty of nature. I look at the latA-s to seek your form and movement; I look into the eyes of startled deers to find similarity with your love-glances; I look at moon to seek your sweet face; and at the feathers of peacocks for your curls. But alas My Beloved, this nature fails to inspire my imagination in scale to your beauty that is etched in your picture on the walls of my heart.” An extremely pristine example of the artist in a dilemma between Naturalism and Expressionism, this stage Hindu artists had already seen, centuries before the European masters would discover it. Similarly, we can notice that what is discovered as Dynamism by the post-renaissance European masters later, as a way of representing movement by simultaneous multiple depiction of the same object, is openly evident in its full glory in the iconography of naTarAja’s arm-movement, or in Rahasalila painting of Kangra, as well as in the famous depiction of buddha ascending the staircase of buddhahood. For the Cubism likewise, see how the jaina architects were able to conceive of a very sophisticated synthesis of pure geometric play of shapes, repeated and patterned across multi-dimensional planes. If only had the European Cubist masters of last century, Picasso and Braque, visited Western India and seen the jaina designs at Shatrunjaya and Ranakpur, they would have immediately found for their Cubism a more sophisticated aesthetic connection with Hindu antiquity!

So we tend to agree with what Husain is saying. Let us continue with Husain’s narrative:

Reader should take a note of Husain’s appeal to Coomaraswamy, and understand his frame of references.

The above is from 1997, when controversy had not yet been heard.

All we can discern from Husain’s verbal narrative in the above is that far from any Leftist sentiment, here is a painter who seeks, or at least claims to seek, a genuine Indian artist tradition.; whose frame of reference is Coomaraswamy not Croce and Picasso; who is tradition-sympathetic, interested in the genuine Hindu chitra-kalA.

That was Husain’s verbal narrative, now let us look at his visual narrative, as we should be able to understand the mind of an artist, a poet, a writer, better through his creation more than his verbal biographic narration, besides as they say, a picture can speak more eloquently than a thousand words.

So let us now get into his art, and for a moment detaching ourselves from the controversy try to understand his visual grammar first. By doing this is how we shall be able to also explore the answers like whether Husain had been deliberately disrespectful to Hindu devatA-s, and why if so, etc.?

Now as far as the criticism of Husain around the controversy is concerned, what is discomforting is the small sample size of Husain’s works being considered. Surely when the painter has created hundreds of pieces, it does not seem fair to only look at a dozen or so of his offending paintings. Then too, almost all the samples have come from a short span of about four middle years of 1970s, and few from 1996-97. For Husain, who had been active for over seven decades, we should look not only for a larger set, but also representative distribution over all the range of years, and understand his work as a whole, including and particularly those paintings that are not offending. And then we would be prepared to understand and analyze something about the offending ones too.

Now, there is only one precaution, indeed a preparation, that one must carry in one’s mind. We should remember that Husain was a modern painter. A modern painter by definition has his own visual grammar, different from the prevailing grammar with which audiences are familiar, therefore, one must be patient with any modern painter to really understand, if not like, the saundarya-bodha of that work. As to this difficulty of any modern artist, Clement Greenburg rightly observes that since a modern painter, “breaks up the accepted notions upon which must depend … the communication with their audiences, it becomes difficult. […] artist is no longer able to estimate the response of his audience to the symbols and references with which he works.”

kAmasUtra says, “सा कविता सा वनिता यस्याः श्रवणेन स्पर्शेन च, कवि हृदयं पति हृदयं सरलं तरलं च सत्वर भवति”, that, in short, a poem and a woman are good (for you) if they melt your heart. But not all poems and not all women can melt all hearts; does it also not depend upon the taste and aesthetic-sense of the perceiver for an art or poem to strike that rasa in his heart? Indeed as is well said by the medieval Hindi poet Bihari, ” मन की रुचि जेती जितै, तित तेती रुचि होय”, that is, his poems can not be liked by all, only those who have a similar aesthetic-liking (ruchi) in their heart that matches his, would find his poems beautiful (suruchi), and for the others it might even sound repelling (kuruchi), but he appeals to the audience to at least understand if not appreciate what he creates. So, in the similar vein, the precaution we need in studying Husain’s art is, to only be sympathetic and open and understanding, not judge it only by our personal aesthetic sense nor by the traditional norms and symbols; one may still appreciate or at least understand an art, a poem, even if one does not find it to their liking or taste; this would be the approach of our traditional rasaj~na AchAryas, and this is how let us look at Husain’s works.

So let us start, theme by theme. As an auspicious beginning, let us start with gaNesha, who seems to have much fascinated Husain and had been his favourite subject on canvas besides his horses. Following are some of the samples of his gaNesha:

1972:

1975:

Early 80s:

From 1984:

From 1993:

From 1998:

And in 1997, on the eve of the 50th Indian Independence day, It is gaNesha whom Husain invited on a symbolic tricolour:

Above are only some samples. There are hundreds (literally) of his colourful paintings and sketches and drawings devoted to gaNesha alone, and a lot more where gaNesha shares canvas with some other central themes. None of his gaNesha depictions seemed offending to our eyes even by any stretch. In fact we also read an interview, where he says he would begin any major painting by first drawing a gaNesha on the canvas, as an auspicious beginning. In some paintings of Husain, indeed gaNesha is just present lurking in some corner although themes are entirely different. Let us remember this fascination of Husain for gaNesha for we shall again refer to this later.

Let us now look at his depiction of the other Hindu deities.

Besides a painting of shiva-pArvatI from 1970s that has been included in the list of “offending”, we could see how Husain has depicted mahAdeva and gaurI on multiple occasions in a variety of styles, and still quite respectfully. Indeed Husain’s first major foray into depiction of Hindu deities started with his painting in early 1960s, titled by him as umA-maheshvara:

Another of his painting depicting the shiva family from the same decade:

Both of the above are aesthetically quite pleasing.

In this watercolour showing a street of Hyderabad in 70s, notice his depiction of umA-maheshvara on a film poster:

He again revisited umA-maheshvara in 70s in this one:

Below is his expression of ardha-nArIshvara form of umA-maheshvarau:

In the following watercolour from 1970s, he depicts shiva is in a female naTinI form, playing mR^ida~Nga and dancing, with kR^iShNa giving him company on flute:

That brings us to kR^iShNa, whom too Husain seemed to have quite adored as a subject, and whose depictions on his canvas have quite a strong emotional appeal. Some samples:

Gopala, 1972:

His depiction of Krishna Lila is not at all vulgar or obscene, indeed there is a strong romantic and mysterious appeal:

Same theme in a different style and format:

Krishna Lila, early 1980s:

And look at this quite powerful pArtha-sArathi presentation in the following oil painting:

In the above one should observe Arjuna shown ready to abandon his gANDIva and jump from the chariot (notice the depression on this side of the wheel); bi-colour sun represents the conflict between dharma and adharma; horses pulling in different directions representing confusion. kR^iShNa, not represented in form but commanding a central presence merely by the symbol; His tarjanI raised upright with sudarshana, and the famous words emitting in devanAgarI. Also do notice another fine point in the above. Because the width of the painting did not allow Husain to place kR^iShNa in the exact center of the painting geometrically, so he finds an artistic way to do it visually. He deliberately paints a different and paler background on the left side, so that kR^iShNa optically becomes the exact center of his painting.

There is another Husain painting on pArtha-sArathi theme, which is considered offending by some. Here it is, though we could not locate a higher resolution version:

One must carefully digest what the painter is depicting in the above. What he has used in the above is an idiomic Expressionist Morphism, using which he sends kR^iShNa to the background, like in the previous one, to participate in the theme symbolically, through a large dark palm making an upadesha-mudrA. Arjuna likewise in background with his bow is morphing into a figure in the foreground. This figure that dominates the foreground is of George Washington with the old version of American flag, leading the revolution and war for American Independence. The foreground is merely to lend the symbols and idiom to the real message which is embedded in the background. Here Husain is trying to portray the war of mahAbhArata as a revolution, a war of independence, of national political integration, and its hero, kR^iShNa, as a Revolutionary, a Warrior, a visionary Leader, and indeed the Founding Father to India as Washington is to the American nation.

Is that not the message of mahAbhArata? One who feels offended by this painting, we must say, has either little understanding of the epic, or can not appreciate such an obvious messages of this modern art, or more likely both.

There are plenty of paintings where Husain depicts kR^iShNa, and to our eyes all of them are quite pleasing, even emotional, and powerful. There are some paintings where a Mother Teresa like figure is shown tendering to boy-kR^iShNa. In Husain’s visual grammar, as we noticed how he utilizes Washington’s attributes to say something about kR^iShNa, likewise in depicting mother, he uses the symbol of a white dhoti with blue border, iconic of Mother Teresa, borrowing the symbol of generic motherhood. Rather than getting offended, we must first understand the painter’s methods.

While on mahAbhArata, following is Husain’s “Bhishma, or the 10th Day on Kurukshetra”, a watercolour on paper, from 1980s, depicting the grandsire:

In above too, notice the powerful usage of symbols. Half Sun, showing the wait of the pitAmaha for the uttarAyaNa; ten window panes, depicting the count of days; and a raised distorted point of illumination raised above the chest, depicting his will over death. Again a powerful depiction to our senses.

Then look at the following collagesque depiction on mahAbhArata themes:

Now devI-s.

What most people seem to have missed noticing is that after the understandably offending paintings, Husain had once again painted the same devI-s in a way that could not have offended any sane minded Hindu, or so we think; and could there be any better way for a painter to make a statement?

Also, those offending ones are not the only depictions of devI-s by Husain. Let us look at some.

This is a 2001 oil on canvas, depicting pArvatI as a mahArAShTrIya woman with a little gaNesha in her lap. This reminded us to the choLa sculptures which often depict her as a typical draviDa housewife carrying a tiny (and truant) gaNesha in one arm while managing ShaNmukha with the other.

This one is different in style but similar in sense:

Following are his depictions of sarasvatI, already in mid 90s when there were no protests yet:

Above is the image of a modern Indian woman, her face, and the confidence that emits through her pose, are all very modern; and yet, she is dressed up in an entirely Indian dress, modern but distinctly Indian. And the painter also shows, symbolically by the flute and the music notes, how the traditional functions and duties of hers she does not abdicate.

This is Husain’s Sarasvati. You may like it, you may dislike it, but there is no disrespect here; indeed it shows only reverence of the painter; and indeed a way of Husain praying to sarasvatI for herself leading the modernization of Arts. Do not miss the symbolism of her lifting the Sun by her right arm, bringing a new dawn; and he is showing how easy it is for her to do, she is not even glancing towards it. And also notice another message: which type of modernization is Husain asking for sarsvatI to bring about? He is not asking sarasvatI to abandon vINA and take up Sitar or Guitar, he still wants her to only play vINA, but just that she now takes up the help of new techniques, new technology: she can print her favourite musical notes on paper! That the forms should be new, looks might be new, technique also new, but the essence continuing to be what has eternally been in the Hindu sphere: vINA remains!

This reminds us of the famous prayer to sarasvatI by Shri Suryakant Tripathi ‘Nirala’, a modernist Hindi poet, who is asking sarasvatI to make everything anew, only the old vINA remains and she remains:

We are with M F Husain in the prayer.

Following is his ‘Sita and the Golden Deer’, from 1991:

Some three depictions of his Hanuman have caused much protests, and understandably so, but let us also look at his other depictions of Hanuman and see them from the eyes of how a modern painter would have looked at the subject.

This above one has also caused some offense as “Hanuman” is shown in such a disgraceful posture. But this is how we read it. First off, one must understnad that the scene is depicting the vAnara-s bringing stones for the setu-bandhana. The watercolour above, depicts not hanumAna but a vAnara (do observe the differences in form, colour, etc.), plucking a huge rock from its base, lifting it up and placing on his left shoulder. We do not see any offense meant in this.

The below watercolour is Husain’s depiction of a Hanuman shrine with female figures performing their devotion:

This below painting has also been considered offensive my some people:

But those who consider the above offensive do not observe the message of it. Here we see a male figure and a female, making a vartula, which is rotating in a whirl with a small Hanuman in its center. The vartula of male and female would easily remind one of the famous Chinese dvaita motif of Yin and Yang. The yang on top, that is the well-formed muscular body, and yin, the female on the bottom. What the painter shows here is the make up and conception of Hanuman, which is why Hanuman is being shown in his infancy; on one side you have the powerful masculine side of his, he is vajra~Nga after all, but on the other side, equally dominant feminine qualities of Hanuman, that is, his devotion, service, sublimity and wisdom; both sides combining to make the concept of what Hanuman is. That is how we read this modern painting.

Below is a painting of his, which he titled as “Vedic”, collagesque depiction of the Hindu religious traditions.

Let us now explore an important attribute of Husain’s grammar, his attitude towards and depiction of Brahmins. After all he is accused of having insulted Hindus by showing a naked Brahmin together with a fully clothed Sultan; so let us try to understand that painting by first going through Husain’s other portrayals of brAhmaNas.

This one is entitled ‘Brahmin’; it is from 1980s: