[1]

“किम्प्रमाणम्?”, demanded an intrigued Bhojadeva.

Bhojadeva, the best exemplar of that Hindu intellectual and cultural flowering, upon which an iron curtain was drawn by the marauding ruffians, as the AchArya of mAnasa-taraMgiNI so astutely puts it, should stand in need of no introduction to the learned Hindus. The rAjan had once commissioned a grand shivAlaya to be constructed, in a new metropolis that he was founding, of which he was himself both the urban planner and the architect, and which metropolis, or whatever has become of it, is known today as Bhopal. Now, when Bhojadeva had grandly and exuberantly renovated the shivAlaya-s of faraway lands not even in his domain, like the famous shrines of kedAranAtha, somanAtha, pashupatinAtha, and a famous shivAlaya in the kashmIra country of which nothing is left anymore, then certainly this one had to be so grand and mesmerizing as to rival, even surpass, the beauty and power of those in the draviDa country constructed by his friend and ally the choLa rAjan. Thus a battery of architects and masons, painters and sculptors, from all over bhAratavarSha, was engaged at Bhoja’s grand shivAlaya project.

The rAjan once rode out to inspect the works in progress. One artist from gujarAta country was busy sculpting the shiva-gaNa-s at the shrine, and had just finished his work on an important member of the shiva-shAsana, bhR^iMgI. But seeing what the artist had sculpted, Bhoja was intrigued, shocked. The artist had depicted him to be starving like a beggar, in tatters almost naked, reduced to mere skeleton with eyes bulging out of sockets, staring in the direction of mahAdeva.

And the learned rAjan, himself the author of the best handbook on Hindu shilpa, chitra, engineering and more, samarAMgaNa sUtradhAra, did not like nor understood the artist’s idea. He was irritated, and naturally so, it was after all the most ambitious shrine that he was dedicating to his iShTadevatA. So the King demanded of the artist, “किम्प्रमाणं?”, what is the proof of your concept?

The startled artist struggled and muttered out some explanation in apabhraMsha tongue, some incoherent explanation, which made no sense to the learned man who had to his credit the composition of eighty-four books, all on different subjects as diverse as medicine and grammar, engineering and yoga, politics and poetics.

A good artist gets used to speaking eloquently through his brush and through his chisel-hammer, so much and so often, that the common faculty of articulation often escapes him, it becomes less and less relevant to him. What the artist tried to explain could not convince Bhoja, who got even more irritated.

One poet from Bhoja’s retinue named dhanapAla decided to intercede. He examined the art, conversed with the artist, and then articulated the artist’s concept through this following poem:

दिग्वासा यदि तत्किमस्यधनुषा तच्चेत्कृतं भस्मना

भस्माथास्य किमङ्गना यदि च सा कामं पुनर्द्वेष्टिकिम।

इत्यन्योन्यविरुद्धचेष्टितमहो पश्यन्निजस्वामिनो

भृङ्गी सान्द्रशिरापिनद्धपुरुषं धत्तेस्थिशेषंवपुः॥

[Since mahAdeva is digambara, (who lives naked and depends on his begging bowl), which property has he (like a vaishya) to protect by keeping a Great Bow as he does? And if he does keep a bow (like a kShatriya), what need has he to smear the ashes (of shmashAna) upon his body (like a sanyAsI)? And if indeed the ashes he must smear upon him, why take a wife (like a gR^ihastha)? And if a wife he must keep, why vanquish the (poor) kAmadeva? Looking at, contemplating upon, but unable to comprehend these and the other great mysteries and ironies in the nature of his Lord mahAdeva, has bhR^iMgI become crazy and malnourished like this (and that, is the concept of the artist.)]

Bhojadeva again examined the art for a few moments in this new light, then smiled apologetically at the artist, “अहो महोदय, गुणाढ्यः शिल्पिनो भवान्!” : “Ah Sir, a good artist you are!”, and thanked the poet for explaining the concept.

This is part of the oral mass of legends of Bhojadeva, a version of which comes to us recorded by the jaina historian merutu~Nga in his chronicle prabandha-chintAmaNi, and the semi-finished, vandalized, grand shivAlaya of Bhoja lies in ruin on the outskirts of Bhopal, almost as a telling memorial to what became of that Hindu intellectual flowering.

There are two layers of difficulty before any artist who wants to say either something new or something old in a new way. The first is, since he has departed from the prevailing grammar and conventions, he requires help from a sympathetic articulator to let his work communicate with his audiences. In absence of this, his art is only able to intrigue and irritate, even agitate, the intended audience. So that is the first difficulty: the audience may not understand what he or she says; this difficulty of the artist in the above legend is solved for him by the poet.

And then there is a second difficulty. Since he is proposing something new, which may be different from the general aesthetic sense and taste of the audience and differ from the prevailing conventions, it may not be liked by them; this difficulty of the artist in the above legend is solved by the aesthetic liberality of the connoisseur, Bhojadeva.

In context of Husain, he is faced with both of the above challenges. At first, his visual grammar, as we had attempted to demonstrate in the previous part, is entirely his own, is modern, although the spirit of his art is quite Hindu, rooted in the Hindu ethos. But being modern, it is difficult to be understood, and what Husain direfully needs but does not find, unlike the fortunate sculptor in the legend, is that sympathetic poet, who can articulate and help bridge the communication gap between his art and his audiences. Which art critic and scholar was, and is, in the field, with one foot firmly grounded in the Hindu tradition and the other in genuine and indigenous modernization, with points of references not in Cézanne and Matisse, but in chitra-sUtra and Abhinava Gupta, to do this articulation for any modern Hindu chitrakAra?

Recall Husain’s lamentation, that there had been no such writer after Ananda Coomaraswamy. Indeed there has been no other Coomaraswamy after Ananda Coomaraswamy, no other Dasgupta after Prof Surendra Nath Dasgupta, no other Hiriyanna after Mysore Hiriyanna. And that lamentation is even more relevant for the education of the artists themselves into our deeper roots and intellectual discovery. For a fertile progress, art too needs a productive and firm intellectual ground. On sand can grow cacti, not nAga-champA.

As to the second difficulty, far from the demands that any genuine modernization of Hindu art makes of its audiences, we find no rasaj~na dhurandhara like Acharya Abhinava Gupta nor the powerful yet learned kalA-vichakShaNa connoisseurs like Bhojadeva Pramara and Krishnadeva Raya. Indeed, not even a depression of their footmarks survive on the mud of the Hindu intellect, or so it seems to our eyes, wrong as we desperately hope to be proved in our pessimist assessment.

So those are the challenges, that can easily lead to confusion for any modernist artist of Hindu art. And we speak not for Husain– he is only a medium for us to highlight the plight of the Hindu chitrakalA tradition, a genuine revival of which had begun by such stalwarts as Acharya Nandalal Basu, but which has since floundered in our view.

We had tried to understand Husain’s tendencies and visual grammar in the last part, by exploring some of his paintings as are directly related with the Hindu themes, keeping the controversial ones deliberately aside, so as to not prejudice our purview. And what we had found there was that there indeed is something lot more to his work than is popularly misunderstood. The artist does not show any general tendency of either being a pervert or being an anti-Hindu- two explanations that are often given to explain his controversial paintings.

Far from it, we saw his tendency to be quite respectful, even positively honourable, towards Hindu culture, it shows his sensitivity and concern for its survival and well-being. And this came across not in one or two of his works, but in a large bulk: after all we had seen no less than Fifty-Seven compositions of his in the last part, and not from any limited or skewed time range: we have seen the samples representative of all decades of his career ranging between 1950 and 2010.

And therefore, the explanation of his controversial paintings, to be either from his motive of insulting the Hindu icons and faith, or of his being a pervert, do not reconcile well with what we saw. Even a u-turn theory is not plausible to explain any change in him, since it was a consistent trend in what we have seen. What is more, it is actually the controversial ones that are very few in comparison and limited in clusters theme-wise and time-wise. Therefore it would make sense to look at those controversial ones afresh to see why Husain painted those, and what could have been his true motive.

In other words, should not, and could not, there be some other and better explanation of his motive behind those controversial paintings, which would reconcile better with his much larger positive work that we have seen?

That exploration would be the aim of this part. That is, to understand his controversial paintings in a new light, in light of this hypothesis that he was neither a pervert and nor was he an iconoclast (known in the western art as Dadaists), and therefore might perhaps have a better motive when painting those controversial ones too. This is a hypothesis of course, which we shall test keeping in mind the principles of sAmAnya nyAya darshana of testing a hypothesis, and for the subject matter itself we shall bear in mind the approach as given in the Hindu Chitra Shastra-s in its spirit.

Now, at this point we must pause to make a disclaimer and a suggestion.

The writer of these lines himself finds those controversial Husain paintings as outrageous and offending to himself. The writer is neither concerned with, nor intends to, justifying those paintings. His scope is limited only to understanding why and how the painter did those. To UNDERSTAND and not to APPROVE is the motive of the writer. If the reader finds difficulty in drawing a line between “Understanding” (as dhanapAla did) and “Approving” (as bhojadeva did), and/or, the reader has either not read the previous part in its entirety, or is not convinced by the writer’s conclusion, that is, that the painter entertained a respectable attitude towards Hindu culture, then we should thank our sudhI reader and suggest him/her to consider stopping here.

[2]

It is no accident that when the Adikavi of Kannada, Mahakavi Pampa, wanted to inaugurate a new poetic era that marked departure from old Kannada to new in the tenth century, he composed ‘samasta-bhArata’, a rendering of mahAbhArata. It is also no coincidence that similarly in Telugu a century later, it was the rendering of mahAbhArata that heralded the beginning of a new era of Telugu by the worthy poet Nannaya, followed by Tikkana and finally Errana. A century after Errana, the Adikavi of Oriya language likewise, Sarala Dasa, when decided to inaugurate poetry in Oriya in the fourteenth century, it is no accident that he too looked up to mahAbhArata alone, and produced its adaptation in Oriya, famed as ‘sarala-mahAbhArata’. And it is also no accident that in modern Hindi likewise, at the beginning of the last century, it is the bhArata alone towards which the first modern Hindi poet Maithili Sharana Gupt looked, when he produced on it dozens of his poetic tomes including ‘jaya-bhArata’, ‘nahuSha’, ‘jayadratha-vadha’, ‘ajita’, ‘anagha’, ‘vaka saMhAra’, ‘sairandhrI’, ‘hiDimbA’, ‘vikaTa-bhaTa’, ‘shakuntalA’, besides his magnum opus ‘sAketa’, a unique retelling of rAmAyaNa by lakShamaNa’s wife urmilA who remained behind during the exile of her husband. It is with help from our epics alone that the National Poet steered the direction of Hindi poetry, convincingly and for always, towards a new poetic standard of modern Hindi true to her saMskR^ita roots and free from the imperialistic residues of arabi-farsi. And it is no accident that the poetry in the laukika saMskR^ita itself was inaugurated in the hoary past, as the tradition goes, with nothing else but the composition of rAmAyaNa by vAlmIki, the Adikavi (and Hanuman).

None of these cultural movements making use of itihAsa as their base were accidents, for our itihAsa-s are the living breaths of a living civilization. Homer recoils from revealing himself to West that has severed its umbilical chord with its spiritual ancient, no matter how many Alexander Popes translate him how many ever times in howsoever beautiful ways; Homer is, for West, dead. But not so the vyAsa and vAlmIki for the Hindus: our itihAsa-s are living itihAsa-s, they are our own story for today and tomorrow, for us that is why vyAsa is a chira~njIvI, he is immortal, and so is hanumAn, and that is why they have always been our bedrock on which to build any new awakening, any new cultural renaissance; for us the itihAsa-s are our divine blessings, and itihAsa-s are prANa of our civilization!

So, now, like in the verbal languages, surely would it not be the itihAsa-s alone which should also breathe prANa into modernizing our visual language? And it was certainly done in past by Hindu artists many times, last well-known case being at the time of Akbar by the Hindu painters from Rajasthana and Jammu and Kayastha artists in collaboration with the Persian painters, when Akbar, newly departed from Mohammedanism, wanted to bring about a new Hindu renaissance. (Some of their product is gathering dust in the museums of Jaipur and Kolkata, while the bulk is smuggled away, decorating those of London and Smithsonian)

Whether or not conscious of any of these facts, more likely not aware of these, for whatever reasons Husain was seriously drawn towards Ramayana and Mahabharata, and wanted to depict both of the epics in their entirety, from back to back, in his own visual language. And this he did, first through over two-hundred paintings on bhArata and over a hundred on rAmAyaNa, spending more than a decade beginning in mid 60s, and then he revisited both of the epics, twice again in his career.

Now whatever be the artistic merit of that work, which is not of relevance to us at the moment, what seems certain is that as far as the artist was concerned, it seems he thought this was his most important work. We see that in 1971 when Husain was invited to exhibit select paintings of his in Europe side by side Picasso, it is twenty of bhArata paintings that he prepared and exhibited. And when he had to ceremoniously paint a canvas with Picasso looking on, it is a collage depicting representative scenes from the different parva-s of bhArata that he painted. So whatever be the worth of his paintings, at least for him his work on the itihAsa-s was his signal and the deepest work.

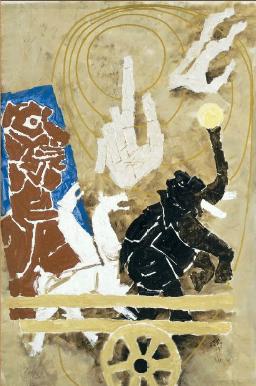

This below is the cover sheet of the leather binding that he designed for his first set of visual retelling of mahAbhArata:

In the above cover, we can clearly see Husain trying to establish his work in the Hindu tradition. For the svasti-vAchana, a famous R^ig-vaidika vAkya from the first maNDala is written on the top. The format of the cover is shown as if it were a leaf from a tADa- or bhoja- patra manuscript. The colour scheme is deliberately black and white to appear like a hoary work. Title is given first in devanAgarI and then in English, but atop the English characters is given the nAgarI horizontal bar, a gesture to remind that the attempted modernization is not altogether imported mindlessly. Beneath it is the familiar figure of the grandsire. Further down are some written words.

The written words are a homage and an acknowledgement by the painter to Shri Chakravarti Rajagopalachari, whose books Ramayana and Mahabharata, as we came across the painter saying in an interview, were his constant companions from which he used to daily read a chapter. And that would explain why it is to pay his gratitude, that Husain quotes a passage from his book ‘Mahabharata’ and prints it in imitation of Rajaji’s own handwriting, complete with an imitation of his signature ‘C. Rajagopalachari’.

Rajaji’s books were, it seems, Husain’s chief references and main sources. But let us also see what else was going on when he began these paintings.

[3]

In the preface to the first edition of his Ramayana in 1957, Rajaji wrote:

“The sophisticated may be inclined to smile where I have often paused in the narration to moralise. To such I must point out that when I wrote the original of these pages I had in my mind always my very young readers.”

But right in the next decade, when Husain began his work on the itihAsa-s, we see that the Hindu zeitgeist had already departed from being satisfied with simplistic understanding of the epics laced with varjanA and moralisation. We can see that the time now was to revisit the itihAsa-s in the original and revise our understanding, explore deeper layers of meanings, re-interpret the narratives, rediscover their values, and contextualize our sense of our itihAsa-s, without being afraid of sophistication and complexity; the “very young readers” of Rajaji were now researchers and retellers.

Already in the same decade we see legendary poet Ramdhari Singh Dinakar rendering Mahabharata in a modernist Hindi poetry ‘Kurukshetra’, through which he questions the validity of the Gandhian pacifism and non-violence extremism. Same poet was to next produce his ‘Rashmi-Rathi’ a poetic rendering of bhArata entirely from karNa’s view-point. Harivansh Rai Bachchan was experimenting with a metrical ‘Jana-Gita’, an imaginative imitation in language and style of Tulasidas, of how the bhakta-kavI would have modernized bhagavad-gItA had he picked his pen for it like on rAmAyaNa. Amrit Lal Nagar was writing his famous ‘Manasa Ke Hansa’ to enter the mind and psychology of the epic-writer himself. History-novelist Chatursen Shastri was writing his epic-novel ‘Vayam Rakshamah’, a Ravana’s narrative of Ramayana, a bestseller for over a decade. Sumitra Nandan Pant in his ‘Purushottam’ and Suryakant Tripathi Nirala in his ‘Ram Ki Shakti Puja’, were seeing Rama as a vulnerable mortal who, by his higher consciousness and commitment to Dharma, rather than due to any super-natural reason, becomes for us an inspiration more than a God-incarnate to be worshipped. Narendra Kohli was writing his famous epic-novel ‘abhyudaya’ where Ramayana is as if a contemporary event, and Rama and Sita as if our neighbours who rise above the rest by their relentless struggle to uphold the values. In a similar vein was writing Bharat Bhushan Agarwal his novel ‘Agni Leek’, as well as an important modern poet Naresh Mehta his ‘Sanshaya ki Ek Raat’, where epics are shorn of all miraculous elements, and their characters have their frailties and weaknesses and doubts and come from our own contemporary mundane world; their events are for us to read as our own story.

It is only because we are more conversant with the literature of Hindi that we give these examples from that language, but otherwise the literary spheres of her sister and cousin languages too were not isolated; the same zeitgeist was making waves there too. Thus we find that in Marathi, Shivaji Sawant was writing ‘Mrityunjaya’ in the same decade, a modern re-interpretation of the Great bhArata from karNa’s view-point, and we see Satyajit Ray attempting to make bhArata’s modern re-interpretation in Bangla, a project which he could not finish, though there was already the shadow of Draupadi on his ‘Pather Panchali’ (1955) earlier, and in Kannada we see the worthy pen of S L Bhyrappa already outstanding in contribution to the same milieu, his magnum opus ‘Parva’, rediscovering Draupadi for modern contemporary context, was to arrive in the same decade of 70s.

And in music also, we see that in the same decade, Mukesh was singing Rama Charita Manasa in an entirely new way, departing from how it was traditionally sung, and by using new tunes and musical techniques, so wonderfully amplifying the rasAnubhava of the original to amazing depths.

They were all genuine national avant-garde of 60s and 70s. Reader should note that this was the cultural current with which Husain found himself connected, not with the leftists who were at this time creating their phony “peoples literature” subsidized by the Soviet. To see what the leftists were doing in field of art, reader may find on internet the dadaist art of F N Souza, especially the likes of his ‘shakti’, ‘blue goddess’ and such paintings and sketches. That is genuine iconoclasm.

We can see the influence of this national zeitgeist on Husain’s thinking, who too was to see his kR^iShNa as a revolutionary statesman and a founding father, as we saw him do in a painting in the last part. We should bear in mind all these currents in middle of which Husain was painting the epics, while influence of Rajaji on him being the utmost as it was, his books being his chief reference and sources.

Then what went wrong?

[4]

His most controversial and provocative paintings include one where Husain has shown Hanuman with a figure of a copulating couple, one where naked Sita is seated near Ravana’s thigh, one where Hanuman is shown without a head, and then the one where naked Sita is shown on Hanuman’s tail.

Those who were saying that these were not outrageous, were either not healthy in their minds, or were not Hindus, or in all likelihood they were perverse Hindu-haters. These paintings are genuinely offending.

But there is this curious question that intrigues our mind. Why only in these paintings did Husain do what he did, since after all he has painted other paintings where Hanuman and Rama and Sita are present. See for instance these following three paintings of his, from three different decades, and three different styles:

[Hanuman a Trimurthi, 1968; depicting Hanuman as devotee of Rama-Sita, and as a warrior and a sage]

[Hanuman a Trimurthi, 1968; depicting Hanuman as devotee of Rama-Sita, and as a warrior and a sage]

[‘Hanuman’s proposal to Sita’, 1979; depicting Hanuman proposing to Sita to take her away from the captivity to Rama. Rama is represented with male motif up-triangle. Signed in Tamil]

[‘Hanuman as Superman’, early 1990s, depicting Hanuman by borrowing the simile of Superman, he is like him tearing his outer self to reveal the inner self. That Hanuman is a superhero, but that beneath the superhero identity is a devotee to Rama-Sita.]

All of the above, and more, are quite respectful portrayals.

It is therefore, and considering his larger work as we saw in the last part, that we are no longer convinced with the simple explanation of his motive in those paintings, that he just wanted to denigrate Sita and Hanuman and therefore he did it deliberately through those outrageous paintings, or that he was a pervert. We must seek some other explanation, some other understanding, which is what we shall now do.

And it is unfortunate, unfortunate for Husain, that all of these paintings come from that single place in the epics, which is the most sacred part of the most sacred kANDa of our most sacred itihAsa. At our place, and we believe it would be the same custom in other regions too, no major work would be taken up by the Hindus without first reciting the sundara kANDa of either Valmiki or Tualsidas, and if that were not possible, then at least that part where Hanuman is himself narrating his exploits in a first person narrative.

And sacred as it is, sundara kANDa is also aesthetically the most powerful portion of all of our literature, not only within the Ramayana, but we dare say, of the entire corpus of both the Ramayana and Mahabharata put together! Maybe perhaps of all our literature put together, both sacred and profane!

Why do we say so? We say so by its most complex and most powerful rasa-vinyAsa, which is almost like a magic, an unmatched literary wonder!

Here, there are not one or two, but six rasa-s out of nine (or eleven as per Bhoja), which are in close play, all at once, and if not simultaneously then in an extremely close proximity and in interrelation to each other. And in these six here, are included all those four exclusive rasa-s, that are called in our nATya philosophy, utpatti-hetu rasa: those which give birth necessarily to some other rasa. And three out of these six, are of absolutely equal strength, which hang in perfect balance taking help of the other three minor rasa-s. And then all of these rasa-s are together made to reach a perfect crescendo at a point, as is simply unmatched anywhere else. But let us understand this.

Let us understand this, for without this we shall not be able to understand the biggest crime, the biggest foolishness, the biggest folly, the biggest failing, and the biggest offense of M F Husain of his entire career, the crime which cost him, as it should have, very dearly. And there is more than depicting Sita naked — that is only at the surface — the real problem of those paintings is at a deeper level.

So, in the original vAlmIki narration, first we have the karuNa rasa (pity), driven by the plight of Sita, serving which in equal strength is the viyoga-shriMgAra rasa (love-separation), driven by Sita’s longing and pining for Rama. That is the first pair.

Then we have the bhayaMkara rasa (terror), driven by the tyranny of Ravana, assisting which is bIbhatsa rasa (revulsion/hatred) driven by his immoral insatiable lust, which vAlmIki paints wonderfully. This is the second pair.

Then, we have the equally strong vIra rasa (bravery) led of course by Hanuman himself, assisting which in equal measures is the raudra rasa (anger, outrage).

Thus, here we have got three pairs of rasa combination: karuNa+viyoga-shriMgAra; bhayaMkara+bIbhatsa; and vIra+raudra.

That in itself is not unique, after all we have in bhArata, the kIchaka saMhAra, and we have many others, but what is unique is the actual effect, which let us try to further understand.

If the rasa-vinyAsa was not already complex, what is more is that the three poles of these rasa-pairs are equally strong and equally dominant. We have the respective proponents of each rasa-yugma — Sita, Ravana, and Hanuman — at once being the strongest characters and highest embodiments of the respective bhAva-lalana. Who can ever be a better nAyikA than Sita, and which woman suffers a plight more acute than hers? And who can ever be a worse and a more powerful villain than the ten-headed tyrant? And who can ever be a better super-hero than mahAvIra? And so strong they are, that they are indeed the very archetype and role-models of the respective rasa-bhAva! And in comparison to each other, they are equally powerful too, able to stand up to one another by their respective strengths.

And there is still more. The rasa-s mix so intricately and so rapidly as if we were on a roller-coaster of emotional anubhUti; in a quick succession the rasa-s influence, ignite, subdue each other and we are quickly transmitted from first to the other to the next sthAyI bhAva. And all of this is packed so compactly in so little transition time — all events occur in a short span of a few hours — that the entire sundara kANDa itself is the smallest portion of Ramayana going by the number of verses and the second smallest by the number of sarga-s! So, all of those rasa transitions take place very rapidly, very powerfully, in a very short span.

And then there is the best of the best, that is the crescendo of all the rasa-s, which vAlmIki detonates in our hearts, in the central scene of the sundara, that is, when the three embodiments of the respective rasa-s actually come together in the same act, physically at the same place: the Ravana-Sita dialogue overheard by Hanuman; that is the point of controlled explosion of deepest rasAnubhUti in our hearts! Till this point, vAlmIki carefully builds up the three streams of rasa-s, one of pity+longing with Sita’s description and lust+terror of Ravan’s description, and the vIra rasa through the bravery and strength of Hanuman, beginning with his being reminded of his latent powers by jAmbavanta, less than a day earlier. And then, with all these rasa-s having been separately built to their utmost maturity, vAlmIki makes them collide at once, and still in a very controlled way, from which he creates a massive build up of outrage which then we live through and then pour through Hanuman’s audacious deeds in the rest of the sundara. That scene in itself is therefore unmatched, perhaps ever in all of our literature; or so is our opinion.

And that is why we say that this is the most complex portion of perhaps all the literatures that we have; no wonder its very name is “sundara”, aesthetic, kANDa!

And that is why Sundara Kanda also does in us the most powerful, most potent catharsis! Sacred as it is, it is also a cure, a visarjana, a nistAraNa, a cleansing and a pathological treatment of many of our inner ills lying dormant in our subconscious! Not without a higher wisdom did our ancestors ask us to do pArAyaNa with sundara kANDa before beginning a major work!! It is not a drama, and if it is, it is a divine drama indeed!!

And this is the scene, painting of which, in the way he did, has sunk M F Husain for ever and always, from which it is impossible for him to ever redeem himself. And we are interested in understanding how and why. If one thinks he simply wanted to denigrate Sita so he did what he did, well, we shall not contest anyone’s opinion, but in our mind we can already see something else going on here.

We have asserted that this scene as vAlmIki has created, as a point of controlled detonation of rasa, is unmatched, and we can observe this, by reviewing how our literary stalwarts have treated it.

mahAkavi kAlidAsa is the very emperor of saMskR^ita poetry, close to whose ability nobody ever came after him, perhaps in any language we might say. How does kAlidAsa, who has churned out such a powerful literature, treat this scene in his raghuvaMsham? kAlidAsa avoids going there at all; limited as his scope is, he is done with this scene in one single shloka in the twelfth sarga of raghuvaMsham. And then too, not by any direct uddIpana, but by utilizing his famous arsenal of upamAna, to describe the situation of Sita being like a saMjIvanI suffering entanglement in a cobweb of poisonous creepers.

mahAkavi bhavabhUti, the master dramatist, is second only to kAlidAsa in the eloquence, elevation of diction and rasa-yojanA. And bhavabhUti shrinks altogether from going there at all. He bypasses the whole scene, by simply having the events indirectly known to the audiences through a dialogue between Trijata and Malyavan, in the opening act of the sixth a~Nka of his mahAvIra-charita. (On a little study of one act of this a~Nka from the standpoint of Hindu drama, reader may see our earlier note on it).

Our favourite poet Tulasidas, the very moon of Hindi poetry, cuts down three out of the six rasa-s, tones down the remaining three, and wraps up the Ravana-Sita dialogue in a meagre ten chaupais and only one doha, without getting into that crescendo of rasa at all. And this he does on purpose. What is more, a sujAna poet as he is, he buffers the scene on two sides, purposefully, to further mild down the effect on the audience; on the preceding side with shAnta rasa through a dialog between Hanuman and Vibhishana, and on the succeeding side with hAsya, by mocking the Rakshasas at the hands of Hanuman’s deeds.

Two renowned poets decide to go there. mahAkavi bhaTTI in saMskR^ita language, and mahAkavi kamban in Tamil. And what do they do?

bhaTTI dares, but he is careful not to disturb the complex chemistry of vAlmIki. He follows the lead of vAlmIki like a child being led by his father holding his finger, and almost exactly retells what vAlmIki has told, in the eighth chapter of his poetry rAvaNa-vadha, only changing the meters and the alaMkaraNa.

And so does mahAkavi kamban. He honestly tells us that he is now daring to go there, and then strictly follows vAlmIki, actually translating to Tamil what vAlmIki has said in saMskR^ita, including his metaphors and similes, and adds his own only to further embellish.

And all these stalwarts did wisely, being totally conscious of the enormity of the task, and knowing the wonder that sundara kANDa of vAlmIki is. And vAlmIki himself lets Hanuman handle the situation and narrate a large part of it — after all Hanuman is himself the ablest poet and wisest grammarian ever. And in mahAbhArata, vyAsa does no different: he has Hanuman himself narrate this AkhyAna when he would meet bhImasena in the araNya.

Therefore, “where the angels fear to tread, the fools rush in”, this proverb comes to mind seeing a foolhardy M F Husain daring to attempt this crescendo of rasa on his canvas.

And what does he do?

[5]

As in drama, so in painting. bharata muni instructs the dramatists and play-writers in his nATya-shAstra, to first practice painting. And mArkaNDeya reciprocates the sentiment in chitra-sUtra, “विना तु नृत्यशास्त्रेण चित्रसूत्रं सुदुर्विदम”, that without knowledge of drama, painting is extremely difficult to grasp. And it is no accident that our best filmmaker Satyajit Ray was a good painter too, and our first filmmaker Dada Saheb Phalke was, few people know, an artist-assistant of Raja Ravi Varma! A good painter has to, he must, thoroughly understand the nuances of drama, for painting is but another expression of the same aesthetic principles in a condensed form. Sage mArkaNDeya says in his pravachana, “यथा नृत्ये तथा चित्रे”.

Reader may recall the concerned painting, that is, one of Sita, Ravana, and Hanuman. We are not going to put that and the other such ashubhadA chitra-s up on our blog. An ashubhadA chitra, which will bring only misfortune to one who paints it, one who sells it, one who buys it, one who displays it, and one who sees it. To the painter it has already sent the ruin of a long career; and the buyer, a well-known American art collector from Boston, died in a car accident hardly months after buying these ashubhadA paintings we are talking about; this we incidentally learnt during our research.

But we digressed. What is the visual design of the painter, and what does he want to do?

Looking at the visual design, it seems, painter is wanting to follow the same rasa-yojanA and the same transitions as done by vAlmIki. He divides the canvas to three almost equal spaces, not geometrically but optically, and wants to dedicate each to the three proponents representing each of the rasa-yugma-s mentioned earlier.

His plan is to follow the transition scheme in the same order, that is, first the plight, then the tyranny, then ending up in outrage. And he wants to do this by taking the viewer’s eye in that sequence from right to left. Why not usual left to right, this we shall soon see.

He first catches the viewer’s eye on the right by the naked Sita. By this he hopes to perform a strong uddIpana of emotional energy, that is of plight. But this vibhAva that he uses, is very loud and very uncontrolled uddIpana, and therefore a very loud and uncontrolled emotional energy instantly appears. However what the painter wants is that it would be that of the sthAyI-bhAva of plight which should emerge, but loud as the uddIpana is, what ends up happening is that it is not the mood of plight that appears in mind, rather it is of outrage that does. We shall return to this; for now let us see what else he visually plans.

Next, the painter has seated the figure of Sita on the left thigh of the central and the largest figure, that is of Ravana. This is what is both an Alambana vibhAva to enhance the mood of plight, as well as, a stimulation for vyabhichArI-bhAva, that is, transition to the next mood, that is of tyranny. So by seating her on the left thigh of the tyrant, the painter’s plan of transition is from the first, that is plight, to the second, that is tyranny. And for this transition, Husain is hoping of using a known Hindu convention. Showing one’s left thigh to a para-strI or asking her to sit on it, is mark of the highest dishonour that is possible in our world to a woman — recall the sabhA-parvan where Duryodhana invites Draupadi to sit on his bare left thigh — and this convention the painter wants to invoke here, as a vyabhichArI-bhAva, to transit the viewer’s mood from plight to tyranny. It is only for using this cultural convention that the painter paints the painting from right to left and not his usual method of left to right.

Then next, he has the central figure, that is of Ravana, in ugliness and ghastliness, frontally confronting the audience, by doing which, the painter hopes this figure to face the wrath of the viewers mood of tyranny and then outrage, that he hopes will now emerge.

Now, if the contact of the left thigh was painter’s plan of vyabhichArI-bhAva, transition from plight to tyranny, he also inserts an active interaction between the two by introducing what is an anubhAva, a deliberate stimuli, of Ravana raising his right arm to hit Sita, as vAlmIki says. By this, the painter hopes to make a close loop between the plight and tyranny, amplifying both, and resulting in further generation of outrage by this interaction.

And then, in order to transit to the third rasa-yugma, he makes Ravana lean to his right, as if to face Hanuman, who is here shown in form of a monkey (as says vAlmIki), shown in anger, ready to pounce on the former. Painter gives an isolated area to Hanuman, and a lot of blank space in that area, and it is in a bright colour, matching the colour of Sita. By this plan, the painter wants the subconscious mood of anger to finally flow and gather here, and then from here, get pointed through Hanuman pouncing at Ravana, towards Ravana.

This is his visual design. But this all is what the painter *hopes* to do. What he ends up doing is terribly different.

In the first place, the uddIpana through naked sItAdevI, fails to evoke plight. And this we say after totally detaching ourselves from thinking that she is even Sita. Even if she is not Sita, and an ordinary woman, or not even an ordinary woman but just a shadow, the female figure does not evoke plight, it first provokes disgust and then outrage in itself. And this happens on its own, without requiring either the Alambana of she being seated on the left thigh or requiring the anubhAva of striking right arm. Both of which though, further amplify the outrage. So, the first mistake from rasa standpoint: a very loud uddIpana, an uncontrolled uddIpana, and wrong type of uddIpana.

Next, the three rasa poles are supposed to adequately counter-balance and support each other. However, in this composition, in comparision to the first rasa-yugma, which in itself ends up in a wrong bhAva, the other two poles are not strong at all. Which is why the emotional energy, that is quite strong, refuses to follow the transition plan that the painter has created to take the audience from the first mood to the next. The transition of vyabhichArI-bhAva is too weak in comparision to the uddIpana of first.

Then, therefore, resulting from the above two, an unending loop of outrage alone remains active, which does not, can not, follow the outlet that the painter has planned for it, since the outlet is too weak to control the intensity of mood that has been evoked; intense as it is, it is also uncontrolled; the painting fails to channelise this energy of outrage through Hanuman’s figure onto Ravana, as the painter was hoping. And therefore, the anger remains, it keeps building, going into no catharsis, and as a result therefore, it has to go into and towards the painting itself, and then towards the painter himself. And it is a very active painting, therefore even more anger is what it generates.

Finally, there is another very unforgivable element on the canvas, that is, there is an unmistakable sensuousness about it. Where is that coming from and why, this is also significant to explore, but that we shall do in detail, a section later.

Now this is what is called an utkaTa painting. In chitra-shAstra, such utkaTa chitra-s are prohibited from being displayed, excepting certain situations. Otherwise, filled with powerful negative energy, they only bring ruin and misfortune to all concerned. And this painting is a living exemplar of it, and a lesson for the aspiring Hindu art modernists.

Then the next two offending Husain paintings of this context are easily understood. One with Hanuman without a head, is the next in sequence, and is to narrate Hanuman’s remorse after having mindlessly burnt the city in his outrage. In vAlmIki’s narration, the plight of Sita has so overtaken Hanuman’s mind, filling it with utter outrage and extreme anger, that the plight of Sita becomes more powerful than Sita herself. So angry is Hanuman by the plight of Sita that while burning the city he forgets all about Sita. But it recurs to him after he has done his deed, and then he becomes remorseful, he curses himself, he calls himself a fool and a sinner. He calls himself a monkey to have not thought that Sita also might get hurt in this fire. And the plight of Sita that was his anger so far is now his remorse. He contemplates whether Sita would have gotten burnt in the fire he has lit, then thinks that to be impossible, but still returns to Ashoka Vatika to check if Sita is alive. This is vAlmIki’s way of shamana of raudra-rasa, extinguishing the outrage, by re-invoking karuNa rasa through remorse. That is what the painter wants to depict, and there is nothing much to explain in it. Headlessness to show Hanuman’s extremely reckless outrage, the mudrA of his left palm, to show his astonishment with himself at his deed.

The last offending painting of this sequence is where figure of Sita is on Hanuman’s tail.

(Most people who were defending Husain have not even understood the painter’s concept, and were defending him! We read an article by one gentleman, who teaches in an American university, where he says in support of this painting that this scene depicts Hanuman’s proposal of carrying Sita back to Rama! There can be no more ignorance and lack of imagination than that!)

In painter’s concept, this painting is meant to be in context of Hanuman leaping across the ocean from Lanka back towards his comrades waiting on this side of the shore, and while he is doing that, his mind is occupied by no other thought but that of the plight of Sita, which is not anger anymore but is a lingering pain. And in painter’s visual design, he wants to depict it like this. The figure of Hanuman is shown leaping from left to right, but while in air his face is looking back to Lanka. His eyes are looking back towards the horizon thinking of Sita. His face is painted in ash-colour, and his face is in deep sad thought. And a figure of Sita is stuck on the tail. But this is a shadow of Sita, as depicted in the first painting, and it is in an ash colour matching Hanuman’s face. What did the painter plan by this? Why Sita on tail? This is what Husain imagined: While Hanuman’s tail was burning with which he had burnt the city, he had felt no pain in his outrage (vAlmIki has Hanuman wonder why his burning tail causes him no pain. He says it is by the grace of his father, of Rama, and of Sita). Now the outrage is gone, and the pain should return, but so engrossed is Hanuman’s mind contemplating at the plight of Sita, that it is this pain of Sita’s plight, not the physical pain of his burnt tail, that is lingering in his mind.

Now this is what the painter *thought*. But the result, besides being outrageous anyway, does the similar mistakes as we understood in the first, the most important being in our opinion, of an uncalled for, unpardonable, and unmistakable sensuousness on the canvas. To that account we shall return.

The last of the list, and from the same context, is the portrait of Hanuman where Husain depicts a copulating couple in the background. Reader may recall a painting we had shared in the last part, where Hanuman is shown as an infant in the center of a Yin and Yang formed by a masculine and feminine body, to depict the make up of Hanuman’s personality of having both the sides as equally dominant. In this painting, and by using the context of the sundara kANDa, painter wants to say something else about Hanuman in a similar vein.

This is his concept: Hanuman is the perfect Urdhvaretan, he is the perfect bramhachArin, and with this, he is also a perfect vIryavAn, he is mahA-vIryavAn, that his every hair, every strand, every pore, is full of vIrya, that a drop of his perspiration is sufficient to procreate makaradhvaja, his son, Hanuman not even being aware of him. And the painter wants to use the context of sundara kANDa, that context when searching for Sita, Hanuman enters Ravana’s palace and the inner chambers that night. He does not like it, it is against dharma, but Hanuman has to go through seeing all the hundreds of women that are sleeping in Ravana’s rooms. And he has to bear with all the ghastly lust of the female demons that he sees there. And he is not in the least affected by it, he does not even feel disgust, only pity. In the painting the couple shown are a rakshasa pair, they are in a dAnavI copulation. Then there are some complex metaphors used in the painting, like a mountain or a desert, and there are more things, which we do not understand. It is because the painter wants to separate the metaphors from the real narrative, that he creates a separate section on canvas by dividing it in two horizontal areas. Top is the real Hanuman, everything in the bottom a metaphor. In top he borrows the idiom from Leonardo da Vinci’s ‘Vitruvian Man’, by showing a small Vinci-like shoulder-projection around Hanuman’s shoulders: to say Hanuman is the embodiment of the Perfect Man imagined by Vinci. In bottom, besides the rAkShasa couple, there is also a small projection ejecting from the navel of Hanuman. This is to show him having fathered a son, makaradhvaja, without maithuna: the projection from naval to remind of the mAnasa birth. Both of the separate events take place the day Hanuman spent in Lanka, first while searching for Sita, and second after arsoning the city. Since the painting is too complex, painter also creates a separate verbal description in a frontispiece painting that accompanies the set.

But before moving on to the next part of the discussion, we would want to emphasize one important point to those who would listen to us.

mahAkavI bhAsa’s popular drama dUtavAkyam is about kR^iShNa going as a peace-emissary to kaurava-s to avoid the war. There is a scene in the drama, in which duryodhana has commissioned a large painting which shows the scene of draupadi’s dishonour as described in sabhAparvan. And to show kR^iShNa down, duryodhana invites him to see the painting. kR^iShNa is a kalA-vichakShaNa, a learned critic, who knows the depths of art. The painting is so large that it takes bhR^itya-s to unroll the rolled canvas before duryodhana and kR^iShNa. Duryodhana, to insult kR^iShNa, praises the painting; after all draupadI was a sister to kR^iShNa. kR^iShNa however does not take offense, far from it, he rather studies the art. Then like a vichakShaNa should, says yes this is a good work of art, there is beauty in it, there is life in it, but let me tell you something more, this is ashubhadA, it will bring ruin. And duryodhana obediently orders the painting to be removed.

We do not understand the depths of the art, but we can safely say this. That, all of these paintings, especially the two of Sita, as well as the last one described, are, in our opinion, terribly ashubhadA chitra-s, inauspicious paintings. They are utkaTa, which have negative active energy. And they are not dead paintings, they have some prANa, like most of Husain’s paintings. One may call it superstition, and we are superstitious, but our shilpa and chitra and nATya shAstra-s all tell us that if a chitra or shilpa or poem or drama can do good, a bad one can also do a terrible harm. And these paintings can only bring misfortune to also those who display it or see it. We shall suggest the well-meaning but ignorant people who have splashed the digital images of these paintings all over the websites and blogs and social media, to remove those bad ones for ever. The actual paintings themselves are nowhere on the display. After the terrible death by a car accident of their owner, an American leather businessman, who had bought these directly from the painter, we understand that these paintings are now in possession of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, California, and there, these are not on display but in the curator’s vault for over a decade now. One should let those remain buried there, and let their digital images better be removed from the Internet-sphere too. This is of course our own opinion, addressed to those who would listen.

[6]

In those paintings it is not the nudity, but a peculiar sensuousness that disturbs our mind; sensuousness is not at all of the sacred variety, which a sane Hindu would instantly understand, but sensuousness with an unmistakabe tinge of profane concupiscence that we can feel is apparent in these paintings. There is more than the physical form that offends; it is in the psychic element of these paintings. And it is this same element that comes across also in those scrawl paintings of devI-s. But it is most amplified in these sundara kANDa paintings. But why? Why so?

We think the answer lies at two levels: in sundara kANDa and in Husain.

We had mentioned earlier the complex and wonderful aesthetic arrangement of the sundara kANDa by vAlmIki. Every sentence, every word, every syllable of the kANDa is a magic. Even the message of Rama that Hanuman delivers to Sita, is the highest example of a love-letter that can ever be written, that Sita faints hearing what Rama has said to her. Every gesture that any character makes is full of layers of meaning. Every simile and every metaphor of vAlmIki elevates our mind to some other universe. It is so beautiful.

And, however, it is also easy for an unprepared reader or listener to go astray if not cautious, not prepared. The rasa, especially where the sthAyI-bhAva of lust is invoked, is built very carefully by vAlmIki. It is present but very well controlled by the great poet. And it is to sub-serve a great purpose. And still, it is possible for an unprepared audience, to not receive a complete catharsis, and not receive the right flavour of rasa as is intended in the text, rather get waylaid by own saMvega, impulses, and go astray.

And this is the reason, perhaps, to our mind, why Sant Tulasidas prays right in the preface of his sundara kANDa like this: “भक्तिं प्रयच्छ रघुपुङ्गव निर्भरां मे, कामादिदोषरहितं कुरु मानसं च”. This is the last line of a beautiful prayer to Rama that he has written in saMskR^ita to inaugurate his sundara kANDa. And do notice what he asks from Rama. He asks devotion for himself, and for the book he is writing he asks it to be free from Lust and such defects — kAmAdi-doSha-rahitaM kuru mAnasaM cha — here “mAnasa” has a dual meaning, it refers both to the mind, as well as to the name of his book, Rama Charita Manasa. And why does Tulasidas think of asking this before starting his sundara kANDa? Because he is not only a self-realized master and bhakta, but he is also a clever rasa~jna poet. He knows the potential trouble a wrong understanding of sundara-kANDa can cause for the audience.

Rajaji likewise, before beginning to translate vAlmIki’s sundara kANDa, also makes this caution quite explicit, and wants his reader to become prepared and alert before getting into this:

“As one reads or listens to this sacred story, one should form a mental image of Seeta in her present state. One can imagine the agony of despair of any good woman who has by misfortune fallen into the power of a lustful man. What must be the state of Seeta, daughter of Janaka and the wife of Raamachandra, in such a predicament? To appreciate Vaalmeeki’s metaphors and similes in this context, one should purify one’s heart and fire it with piety.” [Raamaayana by C Rajagopalachari, 1st ed, PP 218]

That is a wise counsel, a sagacious advice. For, while there is lust carefully treated by vAlmIki, it is by our own faults we might misunderstand it. And there can easily be a gap between the rasa as depicted by vAlmIki and as received by a reader.

And this is explained in detail by the rasa-shAstra dhurandhara AchArya abhinava gupta, who gives us seven reasons why those “vIta-vighnAH pratItiH” can happen. And three of those seven, we find relevant here in how it could have resulted in distortion of Husain’s imagination. First, “प्रतिपत्तावयोग्यता सभावनाविरहुः”, one is incapable of grasping the deeper meaning and getting into the bhAva of the writer; second, “स्वगतत्वनियमेन देशकाल विशेषावेशः”, one’s mind is limited by the limitations imposed by the difference of time and space between him and the writer; and lastly but most importantly, “निजसुखादिविवशीभाव”, that one is helpless by his temperamental inclinations like pleasure etc, therefore receives the rasa in his way, not the way it was meant. This last is very important.

Though Husain perhaps intended well, he picked a very complex subject to begin with, which his art was not up to, but what is more, waylaid by his own temperamental sensuality, he ended up doing blasphemy. This is our considered opinion, the learned reader is free to draw his or her own.

Could he have not known what he had done? To this, we think no he could not have immediately known what he had done. A poet and an artist needs someone else to guide him. In our chitra-shAstra, there is an important step after a painting is complete. The ancient Hindu chitrakAra used to take his paintings to the experts, kalA-vichakShaNa-s, for a review. They used to study the art and critique it for the benefit of the artist and the audience, providing not only their judgement on artistic worth, but also guidance to the painter from their deeper depths of understanding of art. In our times, who were/are the critiques with whom Husain would have worked? Perhaps those, who have no idea of Hindu aesthetics, Hindu rasa-shAstra, Hindu chitra-shAstra, for whom only Cezanne and Matisse are the guides.

However, we think Husain had realized his mistake after the controversy had begun. And he was doing his prAyashchitta by painting the rAmAyaNa all over again in a hundred new paintings. That is how an artist can do the prAyashchitta. And that was his last project, noncommissioned, when the daivI niyati did not let him complete it. We shall perhaps come to see in future his paintings from his unfinished rAmAyaNa series.

But we should explore this sensuality in Husain, which led him astray, just a bit more, which will also explain the other cluster of his controversial paintings, the scrawl like sarasvatI etc.

[7]

Few people know that Shri Aurobindo was, besides other things, also an accomplished art critic. In his journal Arya, he used to regularly write columns on Hindu Art. And he had also written at least two books dedicated to the rejuvenation of a genuine Hindu art, entitled “Basics of Indian Art” and “Significance of Art”, and he used to be in communication with Ananda Coomaraswamy and E B Havell on one hand and the svadeshI artists on the other.

In the early 1920s, Abanindranath Thakur once painted a composition titled ‘Bride of Shiva’. The way it was painted had angered some. An album of this painting and others of Abanindranath was brought before Aurobindo in Pondicherry to take a look. The conversation that took place in the March of 1926, was recorded by a disciple in his diary and published as follows.

Sri Aurobindo: Are these pictures of Abanindranath his latest ones? They have given me a peculiar impression.

Disciple: They are his paintings and portraits since 1923. Do you find that he has deteriorated?

Sri Aurobindo: No. But they all seem to be from the vital world. Of course, all Abanindranath’s paintings are from the vital world. But this time they appear to come from a peculiar layer of the vital plane. I felt something like that vaguely, so I asked the Mother and she pointed out that it was the colouring which was responsible for the feeling or impression.

Disciple: We have many paintings of Nandalal dealing with Puranic subjects. But I find one or two are failures.

Sri Aurobindo: In Nandalal’s paintings you find the background of a strong mental conception; while Abanindra-nath’s paintings are from the vital world. I would like to see some of his earlier works. My idea is that in Abanindra’s case the inspiration from Ajanta is not so strong as that of the Moghul and Rajput schools.

Disciple: Of late he has been leaning more towards the Moghul school. Besides, he has been changing his technique so often that it is very difficult to say which style has really impressed him. His subjects may be such as to suggest Mahomedan influence.

Sri Aurobindo: I do not think that the impression is due to the subject at all. It is due to the peculiar layer of the vital plane to which the pictures belong. For instance, take his “Bride of Shiva”. It is an Indian — a Hindu subject. But it is not the bride of Shiva at all in his painting. If at all it is Shiva’s bride, it is “the bride of Pashupati”: Shiva’s bride from the vital plane.

[Evening Talks with Sri Aurobindo, by A B Purani]

A good painter must paint by being in manomaya koSha, if not vij~nAnamaya. In case of M F Husain, he is all about vital plane, all his paintings are the paintings from the lower prANamaya kosha. Half of his 20,000 plus paintings are all about horses — unbridled, unsaddled, uncontrolled horses — stampeding and running amuck, tirelessly! The other paintings where they are not running, it is because they are hurt and injured! This painter was all about vital! Never forget the vaidika and aupaniShadika imagery of horse which R^iShi dayAnanda and Shri Aurobindo used to explain as to mean prANa or senses.

And this painter was all about prANa. Remember he lived to be over 95. And he was about lower prANamaya. And he was about mUlAdhAra. Remember that besides the horses, of what remains, half the paintings are all of gaNesha. gaNesha, the gatekeeper and the lord over mUlAdhAra. This was Husain’s default base. And gaNesha was his devatA in real sense.

We don’t think, he meant insult to sarasvatI when he painted those scrawl paintings, he just did not have access to sarasvatI, and being an artist he did want that access. His sarasvatI was his frustration. This is not sarasvatI, can not be even the basest level of sarasvatI. And the painter knows that she is not sarasvatI, that is why the painter writes her name in bold! Painter is convincing himself, even as he knows she is not sarasvatI. The whole cluster of those three scrawl paintings are out of this artistic-spiritual frustration, and all of those he had painted at the same time in middle of 1970s.

And in middle of 1970s, having finished the first set of mahAbhArata and rAmAyaNa, Husain was interested in doing yaugika and tAntrika paintngs. In this he would of course not succeed, but his paintings of those period show what he was doing. He was painting bhairavI, he was painting uchcHiShTa gaNesha. We also have come to see a mixed media, a photograph of a painting over a photograph, that is from 1975. In this we can see Husain painting over a photograph of his own sitting naked in siddhAsana. And he shows his mUlAdhAra flared up. We shall not be able to put that picture here for obvious reasons. Then there is another painting of gaNesha, which he titled ‘Frolicking Ganesha’, where Ganesha plays amuck with a canvas that is in the painting, on which there is woman’s sketch. In the same period, same year, he also painted this below, which he had left untitled:

Notice the above, though it is untitled, it is clearly about Gandhi’s experiments with his bramhacharya/sexuality. His upper garment is slipping away. His right palm is restrictive, prohibitive, and doubtful. And mUlAdhAra is symbolically highlighted with dark sphere.

All of this, we think, tell us about that phase when he did those things, and of course he was always driven by sensual energies; that was his base.

And he tried to atone for having sinned, having blasphemed. He then painted dozens, maybe hundreds, of paintings with devatA-s, and respectfully, never doing that folly again. This is how an artist can atone in our opinion. Not by verbal apologies but visual.

We think we can conclude here, we are convinced in our mind that he was not an anti-Hindu, and to denigrate the Hindu deities on purpose was far from his motive on those paintings, offending as those are. That is our opinion.

We can conclude here, but let us end with two of his 1971 paintings from his first set on the great bhArata. These two were in the set which he displayed before Picasso.

We have already seen a couple of Husain’s depictions of pArtha-sArathi theme in the last part. This is another of them, and is here to narrate one episode from the last day of the war, when as soon as returning to the camp arjuna descends from his chariot, it explodes. kR^iShNa then explains to arjuna that his chariot had already been destroyed by the arrows of karNa several days back, but that it was by his yoga-bala that he had sustained it for arjuna. We see in the painting, the concentric elliptical-like shapes encircling the chariot which is held in balance by the playful elephant that is holding the cosmic ball, that there is a bigger chariot than that is visible to arjuna. arjuna is shown as astonished. Elephant stands for the kR^iShNa’s yoga-bala here. Smoke flying away reminds of the exploded ratha.

This is the last in the mahAbhArata set. In this the painter has depicted the period of re-construction after the war is finished. On the right most section we see yudhiShThira depicted as a sagacious monarch, his left palm is shown in a mudrA as if contemplating and discoursing on policy and dharma. In the left sections we see many figures, but the gANDIva of arjuna and gadA of bhIma are most visible, the smaller figures are of the youngest pANDava-s; Arjuna’s right arm is shown as if pushing a boundary with his bow, representing the series of conquests by the four brothers in four directions. In the central section the female figure represents draupadI, who is as if in conversation with a bird that has alighted on her left shoulder, representing that she has at last found peace after the whole sequence of tragedies. There are some bruises on her body, but those are fading. We see a small falling figure in blue, near her thighs, showing that the tragedies were like a labour pain to deliver a new era. The kaliyuga.

Posted on June 27, 2011 at 3:47 am in Art & Sculpture, Commentary, Culture, Scripture, Tradition | RSS feed

|

Reply |

Trackback URL

[Part 2] M F Husain in a New Light: A Hindu Art Perspective

by Sarvesh K Tiwari[1]

“किम्प्रमाणम्?”, demanded an intrigued Bhojadeva.

Bhojadeva, the best exemplar of that Hindu intellectual and cultural flowering, upon which an iron curtain was drawn by the marauding ruffians, as the AchArya of mAnasa-taraMgiNI so astutely puts it, should stand in need of no introduction to the learned Hindus. The rAjan had once commissioned a grand shivAlaya to be constructed, in a new metropolis that he was founding, of which he was himself both the urban planner and the architect, and which metropolis, or whatever has become of it, is known today as Bhopal. Now, when Bhojadeva had grandly and exuberantly renovated the shivAlaya-s of faraway lands not even in his domain, like the famous shrines of kedAranAtha, somanAtha, pashupatinAtha, and a famous shivAlaya in the kashmIra country of which nothing is left anymore, then certainly this one had to be so grand and mesmerizing as to rival, even surpass, the beauty and power of those in the draviDa country constructed by his friend and ally the choLa rAjan. Thus a battery of architects and masons, painters and sculptors, from all over bhAratavarSha, was engaged at Bhoja’s grand shivAlaya project.

The rAjan once rode out to inspect the works in progress. One artist from gujarAta country was busy sculpting the shiva-gaNa-s at the shrine, and had just finished his work on an important member of the shiva-shAsana, bhR^iMgI. But seeing what the artist had sculpted, Bhoja was intrigued, shocked. The artist had depicted him to be starving like a beggar, in tatters almost naked, reduced to mere skeleton with eyes bulging out of sockets, staring in the direction of mahAdeva.

And the learned rAjan, himself the author of the best handbook on Hindu shilpa, chitra, engineering and more, samarAMgaNa sUtradhAra, did not like nor understood the artist’s idea. He was irritated, and naturally so, it was after all the most ambitious shrine that he was dedicating to his iShTadevatA. So the King demanded of the artist, “किम्प्रमाणं?”, what is the proof of your concept?

The startled artist struggled and muttered out some explanation in apabhraMsha tongue, some incoherent explanation, which made no sense to the learned man who had to his credit the composition of eighty-four books, all on different subjects as diverse as medicine and grammar, engineering and yoga, politics and poetics.

A good artist gets used to speaking eloquently through his brush and through his chisel-hammer, so much and so often, that the common faculty of articulation often escapes him, it becomes less and less relevant to him. What the artist tried to explain could not convince Bhoja, who got even more irritated.

One poet from Bhoja’s retinue named dhanapAla decided to intercede. He examined the art, conversed with the artist, and then articulated the artist’s concept through this following poem:

Bhojadeva again examined the art for a few moments in this new light, then smiled apologetically at the artist, “अहो महोदय, गुणाढ्यः शिल्पिनो भवान्!” : “Ah Sir, a good artist you are!”, and thanked the poet for explaining the concept.

This is part of the oral mass of legends of Bhojadeva, a version of which comes to us recorded by the jaina historian merutu~Nga in his chronicle prabandha-chintAmaNi, and the semi-finished, vandalized, grand shivAlaya of Bhoja lies in ruin on the outskirts of Bhopal, almost as a telling memorial to what became of that Hindu intellectual flowering.

There are two layers of difficulty before any artist who wants to say either something new or something old in a new way. The first is, since he has departed from the prevailing grammar and conventions, he requires help from a sympathetic articulator to let his work communicate with his audiences. In absence of this, his art is only able to intrigue and irritate, even agitate, the intended audience. So that is the first difficulty: the audience may not understand what he or she says; this difficulty of the artist in the above legend is solved for him by the poet.

And then there is a second difficulty. Since he is proposing something new, which may be different from the general aesthetic sense and taste of the audience and differ from the prevailing conventions, it may not be liked by them; this difficulty of the artist in the above legend is solved by the aesthetic liberality of the connoisseur, Bhojadeva.

In context of Husain, he is faced with both of the above challenges. At first, his visual grammar, as we had attempted to demonstrate in the previous part, is entirely his own, is modern, although the spirit of his art is quite Hindu, rooted in the Hindu ethos. But being modern, it is difficult to be understood, and what Husain direfully needs but does not find, unlike the fortunate sculptor in the legend, is that sympathetic poet, who can articulate and help bridge the communication gap between his art and his audiences. Which art critic and scholar was, and is, in the field, with one foot firmly grounded in the Hindu tradition and the other in genuine and indigenous modernization, with points of references not in Cézanne and Matisse, but in chitra-sUtra and Abhinava Gupta, to do this articulation for any modern Hindu chitrakAra?

Recall Husain’s lamentation, that there had been no such writer after Ananda Coomaraswamy. Indeed there has been no other Coomaraswamy after Ananda Coomaraswamy, no other Dasgupta after Prof Surendra Nath Dasgupta, no other Hiriyanna after Mysore Hiriyanna. And that lamentation is even more relevant for the education of the artists themselves into our deeper roots and intellectual discovery. For a fertile progress, art too needs a productive and firm intellectual ground. On sand can grow cacti, not nAga-champA.

As to the second difficulty, far from the demands that any genuine modernization of Hindu art makes of its audiences, we find no rasaj~na dhurandhara like Acharya Abhinava Gupta nor the powerful yet learned kalA-vichakShaNa connoisseurs like Bhojadeva Pramara and Krishnadeva Raya. Indeed, not even a depression of their footmarks survive on the mud of the Hindu intellect, or so it seems to our eyes, wrong as we desperately hope to be proved in our pessimist assessment.

So those are the challenges, that can easily lead to confusion for any modernist artist of Hindu art. And we speak not for Husain– he is only a medium for us to highlight the plight of the Hindu chitrakalA tradition, a genuine revival of which had begun by such stalwarts as Acharya Nandalal Basu, but which has since floundered in our view.

We had tried to understand Husain’s tendencies and visual grammar in the last part, by exploring some of his paintings as are directly related with the Hindu themes, keeping the controversial ones deliberately aside, so as to not prejudice our purview. And what we had found there was that there indeed is something lot more to his work than is popularly misunderstood. The artist does not show any general tendency of either being a pervert or being an anti-Hindu- two explanations that are often given to explain his controversial paintings.

Far from it, we saw his tendency to be quite respectful, even positively honourable, towards Hindu culture, it shows his sensitivity and concern for its survival and well-being. And this came across not in one or two of his works, but in a large bulk: after all we had seen no less than Fifty-Seven compositions of his in the last part, and not from any limited or skewed time range: we have seen the samples representative of all decades of his career ranging between 1950 and 2010.

And therefore, the explanation of his controversial paintings, to be either from his motive of insulting the Hindu icons and faith, or of his being a pervert, do not reconcile well with what we saw. Even a u-turn theory is not plausible to explain any change in him, since it was a consistent trend in what we have seen. What is more, it is actually the controversial ones that are very few in comparison and limited in clusters theme-wise and time-wise. Therefore it would make sense to look at those controversial ones afresh to see why Husain painted those, and what could have been his true motive.

In other words, should not, and could not, there be some other and better explanation of his motive behind those controversial paintings, which would reconcile better with his much larger positive work that we have seen?

That exploration would be the aim of this part. That is, to understand his controversial paintings in a new light, in light of this hypothesis that he was neither a pervert and nor was he an iconoclast (known in the western art as Dadaists), and therefore might perhaps have a better motive when painting those controversial ones too. This is a hypothesis of course, which we shall test keeping in mind the principles of sAmAnya nyAya darshana of testing a hypothesis, and for the subject matter itself we shall bear in mind the approach as given in the Hindu Chitra Shastra-s in its spirit.

Now, at this point we must pause to make a disclaimer and a suggestion.

The writer of these lines himself finds those controversial Husain paintings as outrageous and offending to himself. The writer is neither concerned with, nor intends to, justifying those paintings. His scope is limited only to understanding why and how the painter did those. To UNDERSTAND and not to APPROVE is the motive of the writer. If the reader finds difficulty in drawing a line between “Understanding” (as dhanapAla did) and “Approving” (as bhojadeva did), and/or, the reader has either not read the previous part in its entirety, or is not convinced by the writer’s conclusion, that is, that the painter entertained a respectable attitude towards Hindu culture, then we should thank our sudhI reader and suggest him/her to consider stopping here.

[2]

It is no accident that when the Adikavi of Kannada, Mahakavi Pampa, wanted to inaugurate a new poetic era that marked departure from old Kannada to new in the tenth century, he composed ‘samasta-bhArata’, a rendering of mahAbhArata. It is also no coincidence that similarly in Telugu a century later, it was the rendering of mahAbhArata that heralded the beginning of a new era of Telugu by the worthy poet Nannaya, followed by Tikkana and finally Errana. A century after Errana, the Adikavi of Oriya language likewise, Sarala Dasa, when decided to inaugurate poetry in Oriya in the fourteenth century, it is no accident that he too looked up to mahAbhArata alone, and produced its adaptation in Oriya, famed as ‘sarala-mahAbhArata’. And it is also no accident that in modern Hindi likewise, at the beginning of the last century, it is the bhArata alone towards which the first modern Hindi poet Maithili Sharana Gupt looked, when he produced on it dozens of his poetic tomes including ‘jaya-bhArata’, ‘nahuSha’, ‘jayadratha-vadha’, ‘ajita’, ‘anagha’, ‘vaka saMhAra’, ‘sairandhrI’, ‘hiDimbA’, ‘vikaTa-bhaTa’, ‘shakuntalA’, besides his magnum opus ‘sAketa’, a unique retelling of rAmAyaNa by lakShamaNa’s wife urmilA who remained behind during the exile of her husband. It is with help from our epics alone that the National Poet steered the direction of Hindi poetry, convincingly and for always, towards a new poetic standard of modern Hindi true to her saMskR^ita roots and free from the imperialistic residues of arabi-farsi. And it is no accident that the poetry in the laukika saMskR^ita itself was inaugurated in the hoary past, as the tradition goes, with nothing else but the composition of rAmAyaNa by vAlmIki, the Adikavi (and Hanuman).

None of these cultural movements making use of itihAsa as their base were accidents, for our itihAsa-s are the living breaths of a living civilization. Homer recoils from revealing himself to West that has severed its umbilical chord with its spiritual ancient, no matter how many Alexander Popes translate him how many ever times in howsoever beautiful ways; Homer is, for West, dead. But not so the vyAsa and vAlmIki for the Hindus: our itihAsa-s are living itihAsa-s, they are our own story for today and tomorrow, for us that is why vyAsa is a chira~njIvI, he is immortal, and so is hanumAn, and that is why they have always been our bedrock on which to build any new awakening, any new cultural renaissance; for us the itihAsa-s are our divine blessings, and itihAsa-s are prANa of our civilization!

So, now, like in the verbal languages, surely would it not be the itihAsa-s alone which should also breathe prANa into modernizing our visual language? And it was certainly done in past by Hindu artists many times, last well-known case being at the time of Akbar by the Hindu painters from Rajasthana and Jammu and Kayastha artists in collaboration with the Persian painters, when Akbar, newly departed from Mohammedanism, wanted to bring about a new Hindu renaissance. (Some of their product is gathering dust in the museums of Jaipur and Kolkata, while the bulk is smuggled away, decorating those of London and Smithsonian)

Whether or not conscious of any of these facts, more likely not aware of these, for whatever reasons Husain was seriously drawn towards Ramayana and Mahabharata, and wanted to depict both of the epics in their entirety, from back to back, in his own visual language. And this he did, first through over two-hundred paintings on bhArata and over a hundred on rAmAyaNa, spending more than a decade beginning in mid 60s, and then he revisited both of the epics, twice again in his career.

Now whatever be the artistic merit of that work, which is not of relevance to us at the moment, what seems certain is that as far as the artist was concerned, it seems he thought this was his most important work. We see that in 1971 when Husain was invited to exhibit select paintings of his in Europe side by side Picasso, it is twenty of bhArata paintings that he prepared and exhibited. And when he had to ceremoniously paint a canvas with Picasso looking on, it is a collage depicting representative scenes from the different parva-s of bhArata that he painted. So whatever be the worth of his paintings, at least for him his work on the itihAsa-s was his signal and the deepest work.

This below is the cover sheet of the leather binding that he designed for his first set of visual retelling of mahAbhArata:

In the above cover, we can clearly see Husain trying to establish his work in the Hindu tradition. For the svasti-vAchana, a famous R^ig-vaidika vAkya from the first maNDala is written on the top. The format of the cover is shown as if it were a leaf from a tADa- or bhoja- patra manuscript. The colour scheme is deliberately black and white to appear like a hoary work. Title is given first in devanAgarI and then in English, but atop the English characters is given the nAgarI horizontal bar, a gesture to remind that the attempted modernization is not altogether imported mindlessly. Beneath it is the familiar figure of the grandsire. Further down are some written words.

The written words are a homage and an acknowledgement by the painter to Shri Chakravarti Rajagopalachari, whose books Ramayana and Mahabharata, as we came across the painter saying in an interview, were his constant companions from which he used to daily read a chapter. And that would explain why it is to pay his gratitude, that Husain quotes a passage from his book ‘Mahabharata’ and prints it in imitation of Rajaji’s own handwriting, complete with an imitation of his signature ‘C. Rajagopalachari’.

Rajaji’s books were, it seems, Husain’s chief references and main sources. But let us also see what else was going on when he began these paintings.

[3]